The

workmen could not believe what they had found.

Digging in Paris , France France . For these were the remains of large

elephants, and elephants, as any rational man understood, lived only in Asia,

or in Africa, not in Paris, France, unless they belonged to the circus. And yet here was evidence that in Paris ’s distant past,

elephants roamed the countryside freely, and made it their natural

habitat. But the workmen were about to

encounter an even bigger shock. For when

the bones were inspected by Georges Cuvier, a young naturalist employed at the

local natural history museum, he announced that they belonged to a species of

elephant unlike any that presently existed in the world. What the workmen had in fact discovered was a

lost world, one totally unlike our own, which had existed at some remote age,

and had disappeared in the distant mists of time. It would be the first of many “lost worlds”

unearthed and unleashed upon a perplexed generation, who would be forced to

reexamine its most cherished beliefs about creation, about life, and about our

ancient history. The legacy of these

“lost worlds”, in fact, would be to shake the modern world to its core, forcing

its people to rethink their place in the universe, their destiny, and their

very reason for existence.

George Cuvier’s shocking

announcement about the existence of an extinct elephant species that had

formerly lived in Paris, France would be the first of many in his long,

distinguished, and controversial career.

He was not afraid of controversy, or of challenging the orthodox views

of the establishment. He was, after all,

working in the employ of one of the most revolutionary figures of modern times,

Napoleon Bonaparte. And Napoleon’s

enthusiasm for scientific discovery was nearly as great as his enthusiasm for

world conquest. When Cuvier encountered

the remains of reptiles and other species that had been unearthed in a French

gypsum quarry, he would also declare that these belonged to creatures that no

longer existed on the earth. And when

the army of Revolutionary France shipped to Paris from the Netherlands a pair

of fossil jaws more than three feet long, which others had suggested were the

jaws of a whale, Cuvier proclaimed instead that they belonged to a huge,

extinct marine lizard. But his most

memorable announcement came when the fossil remains of large winged creatures,

discovered in Germany, were brought to his attention. He identified these as belonging to an

ancient species of flying reptiles, which he named “Pterodactyls”.

The existence of fossils, and of

mysterious creatures unfamiliar to the peoples who had discovered their

remains, had been known long before Cuvier’s time. In previous centuries, they were often

assumed to be the remains of animals that still existed, in some unknown region

of the world, but that no longer lived in the place where they were found. But around the year 1500, some persons began

to suggest that these fossils were evidences of prehistoric plants and animals

that had become extinct. Others contended

that they were freaks of nature. And

those with a more religious disposition even argued that fossils had been

created by the devil, to confuse the pious.

But in the 1700’s religious authority was breaking down, particularly in

France, and as new fossils were being unearthed in the early eighteenth

century, these were looked at in a fresh light.

In 1820, an English surgeon and amateur fossil collector named Gideon

Mantell was visiting a patient in Sussex.

His wife, who had accompanied him on the trip and shared his hobby of

collecting fossils, discovered what appeared to be a large tooth in a piece of

sandstone. Mantell returned to the area

many times after this initial discovery, and asked the workmen employed in the

local rock quarry to alert him to any unusual fossil finds. The men discovered more teeth, along with

some bones, including parts of a huge one, and Mantell concluded that these

belonged to one or more very large reptiles.

Other experts, including Cuvier, disagreed with his conclusions, but

Mantell was convinced that he was right.

Comparing the teeth that he had found with those of living reptiles, he

found a close match with the Central American iguana. But based upon the size of his fossilized

teeth, Mantell asserted that this extinct reptile must have been over fifty

feet long. Other amateur fossil hunters

also took up the art of reconstructing their finds, but many didn’t share

Cuvier’s and Mantell’s talent for anatomy.

Thomas Jefferson, for example, upon finding the remains of a very large

animal, declared that it belonged to a huge prehistoric lion. Other experts later realized that what he had

actually found was an extinct giant sloth, but they still credited him with the

discovery, naming it Megalonyx jeffersoni.

| Iguanodon (Lifesize Replica) |

Cuvier set about to explain what had

happened to these ancient monsters, and considered three possibilities: 1) they

had become extinct, 2) they had evolved over time into some different type of

animal, more familiar to the modern world, or 3) they were still around, but

had migrated to some other region. The

first two explanations were still controversial to his more religious

contemporaries, because they seemed to contradict the Bible, such as

Ecclesiastes 3:14 which says, “"I know that, whatsoever God doeth, it

shall be forever: Nothing can be put to it, nor any thing taken from it. . .

." Cuvier tended to favor the

extinction idea, which even found some acceptance among believers of the Bible. After all, they contended, it must have been

some terrible catastrophe that killed off these creatures, and what greater

catastrophe was known to man than the Biblical Great Flood? And it was easy to imagine Noah shrinking

from the task of dragging some of these monsters aboard the Ark. But the idea that these animals must still be

around was the least controversial to many.

Even Thomas Jefferson considered this explanation: when he dispatched

Lewis and Clark to explore the wilds of North America, he fully expected them

to find living specimens of at least some of his fossils.

|

| Biblical Extinction Theory? |

Civilization in the nineteenth

century was prepared to take a fresh look at the world, its origins, and its

place in the universe. Revolutions in

scientific thinking, led by Kepler, Copernicus, Galileo, and Newton had

demonstrated, in the 1500’s and 1600’s, not only that the world was not at the

center of the universe, but that the universe itself obeyed fixed, immutable

laws. The motions of the planets, the

force of gravity, and other great natural phenomena which had mystified and

awed mankind from the earliest times could now be explained in terms of

mathematical equations and geometrical relationships. In the 1700’s, the Age of Enlightenment

introduced a new crop of thinkers and revolutionaries, such as Voltaire and

Rousseau in France, Jeremy Bentham and David Hume in Great Britain, and

Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson in America, who sought to build on these

scientific advances by creating a whole new outlook based on rational thought,

rather than religious faith. Freedom of

thought and expression were championed in political and cultural life, while

science was relied upon as the ultimate guide in explaining the workings of

nature, and even human behavior itself.

These revolutionary thinkers were impatient for change, and yearned for

an understanding of things based on open-minded contemplation and careful

experimentation.

Even long before the Age of

Enlightenment, people had contemplated alternative explanations for how the

earth began, and how life had arisen on it, which departed from the Creation

myths that were traditionally believed and accepted by the population at

large. The Greek philosopher

Anaximander, who lived more than two thousand five hundred years ago, suggested

that animals change over time in order to adapt to new environments, with new

species arising out of old ones, and that even human beings had descended from

some different type of animal. But by

the 1700’s, new perspectives, new ideas, and new discoveries came together to

produce a more general challenge to orthodox views of creation. In France, the philosopher Denis Diderot

entertained his own ideas of evolution, proposing that life arose spontaneously

on earth, and that new animals appeared through random mutations of existing

ones. “Who knows,” he once wrote, “if

this is not the nursery of a second generation of beings, separated from this

generation by an inconceivable interval of centuries and successive

developments?” The French astronomer

Pierre Laplace, building upon Isaac Newton’s theory of gravitation, and his

ideas on how stars had been formed through gravitation, produced a model of the

universe which explained how the earth and other planets came into being, by

condensing out of rotating clouds of hot gases, or nebula. It is said that Napoleon Bonaparte once

listened to Laplace’s theory of creation with great interest, but was moved to

ask him where God fit into it. To this

Laplace replied, “I have no need for God in my hypothesis.” Evolutionary thinking received another spur

in the eighteenth century with the birth of modern geology. The German scientist Abraham Werner, studying

rock strata, argued that the earth’s geological features had been formed by the

gradual retreat of a worldwide ocean.

While his theory suggested that the earth was much older than

theologians believed, it also lent support to those who argued that species had

become extinct because of the Great Flood.

But Cuvier, in his studies, had realized that different strata of rocks

contained entirely different fossils. He

believed, as had the ancient Egyptians, that there had been more than one great

flood. For Cuvier, however, this was not

proof of evolution, only that each age saw the preponderance of different

survivors. His more religious-minded

followers went further, arguing that perhaps there had been fresh acts of

divine creation after every great deluge, as if God was trying a different

design, to replace the one that He had just erased. But there were challenges to Werner’s view of

geologic history. In 1795, a Scottish

geologist, James Hutton, published a book called the Theory of the Earth,

which explained its features in terms of continuous and gradual geologic

processes, rather than catastrophic ones.

This was a fatal blow to the ideas of Cuvier and his followers, but not

to evolutionary thinking. In fact, it

paved the way for a radical new explanation of why different life forms seemed

to appear in successive ages of history.

By the early 1800’s, the idea of evolution was “in the air”, but nobody had been able to make a case compelling enough to win the general approval of scientists and intellectuals, and capture the popular imagination as well. What was needed was a mechanism: something that explained how new and different kinds of plants and animals could appear on the earth. A bold attempt at creating such a mechanism was made by one of Cuvier’s own employees at the French natural history museum, the Chevalier de Lamarck. Lamarck argued that simple organisms were being created all the time by some natural life force, interacting with physical matter on the earth. And then, these organisms evolved and changed by passing on, to future generations, beneficial characteristics that they had developed during their lifetimes. Lamarck pointed to the giraffe as a prime example, contending that generations of stretching their necks to reach foliage in tall trees had resulted in long necks being a permanent feature of their descendants. But Lamarck’s hypothesis was easily refuted by critics. If one were to cut off the tail of a mouse, for example, all of the mouse’s descendants would still have tails. What, then, did account for the giraffe’s long neck, or the elephant’s snout, or the ability of birds to fly? A new, more compelling explanation would come from a British naturalist.

Born in England in 1809 to a

prosperous family, Charles Darwin initially aspired to follow in his father’s

footsteps, as a physician. But while in

medical school, he realized that the practice of medicine sickened him: he couldn’t

stomach dissection, detested surgery, and cringed at the sight of blood. He transferred to Cambridge, to prepare for

an alternate career as an Anglican minister, where he found himself drawn to

the study of natural history. At the

recommendation of his professors, he embarked on a voyage that would change his

life, and radically impact his society’s views about the origins of life on

earth. During his five-year voyage, on

the Beagle, Darwin visited the Galapagos Islands, and was impressed by

what he saw. For in spite of the fact

that there were only a few basic types of plants and animals on these islands,

he observed that each type took on a wide variety of forms, as if each variety

had branched out from a common ancestor.

And yet, in spite of this evidence for some type of evolutionary

process, Darwin still could not explain how it happened. For years after his return from the voyage,

he reflected upon his observations, and searched for an explanation. The breakthrough came in 1838, after he read

an essay by Thomas Malthus, an Anglican clergyman, on population growth. Malthus’s essay painted a very gloomy picture

of human society, which had been influenced by his observations on poverty and

destitution in the cities. Malthus

argued that as human population growth outstripped the food supply, which it

inevitably did, only the fittest could survive, and the others would be left to

die of starvation or squalor. Darwin

applied this idea to his observations on the Galapagos Islands. He realized that within any species there is

always variation among its individual members, and that those who were best

adapted to the environment would tend to live long enough to reproduce. Just as there are a wide variety of domestic

dogs and cats, created through careful selective breeding, there is a type of

“natural selection” in the wild that encourages the development of specific

characteristics which make a species better suited to its environment. What Darwin had come upon was a practical

mechanism that would explain not only how species change over time, but also

how new species might evolve out of existing ones. He would wait for nearly two decades before

sharing his ideas in a landmark book, On the Origin of Species, in 1859,

but upon its publication, the idea of evolution would take a far-reaching and

permanent hold on civilization.

|

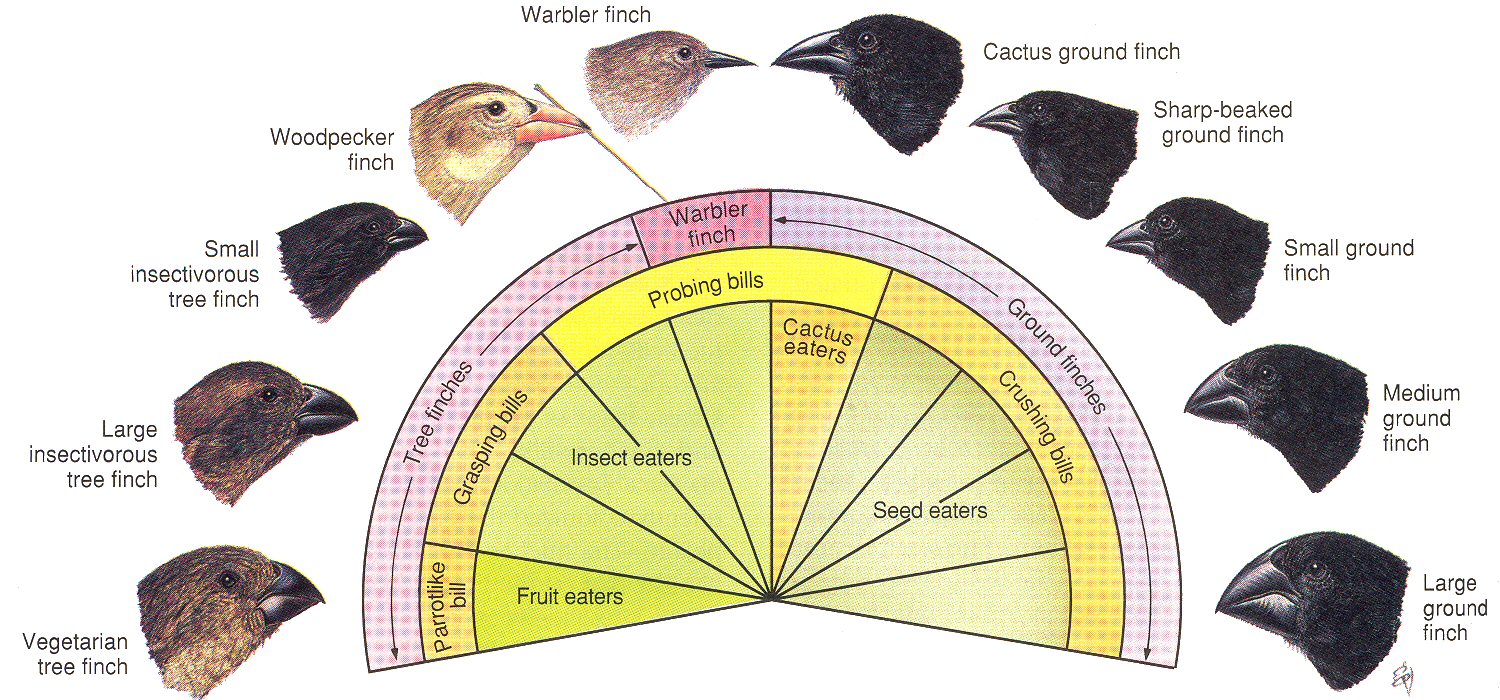

| Darwin's Galapagos Finches: A Case Study in Evolutionary Adaptation |

The book became an instant

sensation, in Europe and America - what we would call today a “runaway

bestseller”. Even liberal members of the

clergy, who had been coming around to the idea that the earth was much older

than the Old Testament would lead its readers to believe, and that its account

of creation did not necessarily have to be taken literally, gave Darwin’s book

a sympathetic reading. But while the

book did not create the firestorm of controversy, at least back then, that many

of us today might have expected, it also did not, as many might believe, claim

to prove the theory of evolution.

Instead, it merely gave a practical and believable account of how

evolution could have happened, and for the more scientifically minded of

Darwin’s age, this was good enough. In

the new age of rationalism, science, and technological progress, here was

emerging an alternative story of the earth’s creation, of the origin of life,

and of the emergence of humanity, that fit right in, with its natural laws,

impersonal forces, and logical relationships.

And over the following decades, those mysterious monsters preserved in

the fossil record, giant winged lizards, sea serpents, woolly mammoths,

saber-toothed tigers, and dinosaurs, took a comfortable place in the popular

imagination, as denizens who lived in a land before time.

But amidst the euphoria over this

new, scientific explanation of life’s origins, which demonstrated to so many

the victory of the rational, enlightened mind over myth and superstition, a

nagging, uncomfortable question began to emerge. If human beings were not created by God, and in fact if they were the product of impersonal laws and forces, then did they actually have a

purpose for being here? Science had

removed the earth from the center of the universe, and man from the center of

the creation story. What was left? And was there even a need to believe in God

at all? After all, the events that made

up the history of the universe, and of the earth, were beginning to look like

the workings of a great mechanism, like a clock, with every part moving in

accordance with the physical laws that controlled it. Was God nothing more than the “watchmaker”,

building it, winding it up, and then standing back and letting it run on its

own? Did God occasionally intervene,

setting things right when certain events didn’t unfold according to his

liking? And was his presence necessary

to build this great mechanism in the first place? If not, it seemed that if God existed at all,

He might be nothing more than a passive observer, who played no significant

role in the events of the universe whatsoever.

The traditional creation story, the

drama that gave humanity a central role in the universe, along with a purpose,

was under siege, and great thinkers of the day tried to fill the void. To restore meaning into a lifeless,

mechanistic existence, they challenged the ultimate reality of that existence

itself. The German philosopher Immanuel

Kant argued that the visible world, the world of time and space, which followed

immutable laws of cause and effect, was merely phenomenon, created in large

part by the minds that perceived it, and that beyond this apparent reality was

something more real, something which transcended physical laws. Other philosophers, building upon Kant’s

insights, suggested that the forces of evolution were actually manifestations

of a universal will, or mind, and that human beings, with their unique

capabilities of intelligence, represented the culmination of this process,

through which the will or universal mind could turn back upon itself with

enlightened reflection. But setting the

human mind at the pinnacle of evolution, while seeming to restore a special

place for mankind in the history of the world, also generated new

controversies. In the emerging science

of psychology, Sigmund Freud, one of its greatest pioneers, demonstrated that

the mind is a house divided, and is driven by powerful unconscious drives and

desires, which often seem to set it against itself, crippling it with neuroses

or compelling it to perform destructive acts.

Freud suggested that civilization - that supposed crowning achievement

of human thought - actually exacerbated this internal conflict. Primal desires: rage, sexual lust, and fear

existed side by side with rational thought, and often overpowered or paralyzed

it, and even directed it to anti-social ends.

Guilt brought on by internal conflict of basic desires with social

conventions and morals was often the catalyst for these internal

struggles. If the human mind was the

final product of evolution, then far from transcending what had come before it,

the mind only seemed to perpetuate the conflicts, strivings, and struggles that

had made evolution possible.

Nevertheless, evolution became the

cornerstone of new worldviews in the nineteenth century. Philosophers such as G. W. F. Hegel and

Herbert Spencer saw the growth of civilization itself as a sort of evolutionary

process, and attempted to extract a blueprint based upon it for the destiny of

humanity. At the same time, many

scientists recognized, and even embraced, the harsh realities that lay beneath

natural selection and survival of the fittest.

As Darwin himself observed, behind the beauty and complexity of nature

existed a desperate and often brutal struggle for existence, which entailed

competition, the threat of starvation, and the predation of stronger creatures

upon weaker ones. Biologists such as

Ernst Haeckl saw these same processes reflected in business competition, the

rivalry between nations, and even the relative success of the different races

of mankind. For Haeckl, a German, the

white race represented the pinnacle of evolution in the human plane. He, along with other scientists, attempted to

give racial and ethnic prejudice, along with national chauvinism, a scientific

pedigree. In an age of industrialism and

nationalism, they lent an air of legitimacy to the predatory and exploitative

practices of business capitalists, and to the growing militarism of European

nations, such as Germany, as expressions of “social Darwinism”. And out of views such as these emerged a

pernicious new blueprint for the advancement of civilization: eugenics, or

selective breeding of human beings to produce a superior stock. Eugenics would take many different forms in

the decades that followed, with some being particularly hideous, and would even

influence social policies in the United States in the early twentieth

century. A policy of sexual segregation

was imposed upon certain classes of “dysgenic” people, and at one time

thirty-five U.S. states had programs of compulsory sterilization targeted to

genetically suspect groups such as the mentally retarded, the mentally ill,

habitual criminals, and persons who suffered from epilepsy. American immigration policy also fell under

the influence of eugenics for a time, as laws were passed to limit the influx

of persons who were not of “Nordic” ancestry.

But it was in the

| The Roaring '20s |

The opposition of American

fundamentalists to evolutionary thinking erupted into open conflict, and a

public crusade, in the 1920’s.

Compulsory high school education in this country was becoming a common

thing at that time, and religiously conservative parents were angered to see

that their children were being taught evolution in the classroom, which to them

was nothing less than a form of indoctrination into views hostile to faith. And in the minds of these Christians, the poisonous effect of Darwin’s influence could already be seen everywhere. This was, after all, the “Roaring Twenties”,

when it seemed that the entire nation was caught up in a tidal wave of greed,

vice, moral laxity, and lawlessness.

People of all walks of life were investing their own money, and borrowed

money, into the booming stock market, on the hope of finding an easy path to

wealth and a life of luxury. And in

this, the “Jazz Age”, young men and women publicly flouted the moral codes that

had been so revered by their religious parents.

“Speak-easy’s” flourished, where thirsty patrons happily ignored the

national Prohibition against alcohol, and these in turn contributed to the rise

of an organized crime empire in the United States, run by flamboyant

“gangsters”, such as Al Capone. For

fundamentalists the connection was clear: as the beliefs and traditions that

inspired faith in the moral principles of Christianity were undermined by

science – and in particular the science that questioned God’s central role in

the creation of the earth, and of humanity – an inevitable consequence was a

general crumbling of the ethical foundation that supported civilization. For any who doubted them, they could point to

other things that clearly had a connection with Darwinism, like the eugenics

movement, the ruthless business practices of industrialists, who often defended

their tactics in Darwinist terms, and the militarism of foreign nations, such

as Germany, where the influence of Ernst Haeckl and others had inspired its

leaders to view international politics as an evolutionary struggle for

dominance.

The focal point for America

The trial, which lasted for eight

days, was one of the most bizarre in American history. It was a “show trial” in every sense of the

word, covered by more than two hundred reporters from the United States and

Europe, many of whom sat in a special section reserved for them in the

courthouse; it was broadcast live over the radio, and filmed for newsreels that

were sent out to theaters daily. John

Scopes, the alleged defendant, had never actually been arrested, and spent most

of his time before the hearing giving interviews and making public speaking

appearances. And the climax of the court

proceedings came when Clarence Darrow invited his opposing attorney, William

Jennings Bryan, to take the stand as an expert witness, to defend the anti-evolution

statute. Darrow held the literal

interpretation of the Bible up to ridicule, challenging Bryan to defend, among

other things, Old Testament accounts of Eve, the first woman, being created

from one of Adam’s ribs, and of the prophet Jonah spending three days and three

nights inside the belly of a fish. It

made for an entertaining spectacle, and cast the fundamentalists in an

embarrassing light, but in the end it did not lead to victory for Darrow and his

allies. Darrow had actually wanted Scopes

to be found guilty, so that he could take the case to the Tennessee Supreme

Court and challenge the constitutionality of the law. But when the case was heard there, the Court

overturned the guilty plea on a technicality, enabling it to keep the law intact. And after the so-called “Scopes Monkey trial”

did not lead to a repeal of the anti-evolution law, other states and school

districts felt emboldened to pass their own versions of it.

|

Although the religious opponents of

evolution ultimately failed to ban its teaching in public schools,

fundamentalism, as a challenge to the scientific world view, did not pass

away. Because while the proponents of

science claimed that they had freed the world of dogma, superstition, and

ignorance, what they never succeeded in doing was to give civilization a new

destiny and purpose for mankind.

Religion, and myth, offered to every individual a reason for existence,

a purpose, and an ultimate goal. A

clockwork universe offered none of these, replacing the design of a beneficent

Creator with a lifeless, mechanical machine.

And while evolution seemed to restore the idea of progress to life, and

perhaps even an ultimate end, it at times seemed to be an amoral end, achieved

through the brute processes of competition, predation, and exploitation. As many persons looked upon the new age of

modernity, they saw confusion, a lack of moral bearings, and the products of

scientific invention applied to blatantly immoral ends. The gains bestowed upon civilization by the

light of reason seemed to be more than offset by the horrors of an impersonal

technology, turning human beings into factors of production, and giving the few

who enjoyed real power awesome and terrifying means of repressing their

subjects, and destroying their enemies.

Religious fundamentalism, rather than fading away, has remained with us

to this day, and its influence is even more pervasive now than it was a hundred

years ago. It exists as a significant presence among all

faiths, Christians, Moslems, and Jews alike, and has become a political force,

and in some countries a military force, that has exerted itself in ways that

have transformed the international landscape.

We react to the behavior of fundamentalists in other nations and cultures

with horror and condescension, while having to acknowledge and contend with

their powerful influence in our own.

During its brief history, America

has tried to reconcile two great forces that have defined it as a culture, and

shaped it as a society. On the one hand,

there is that persistent strain of religious fundamentalism, obstinately

resisting the more secular strains of civilization. On the other hand, there has been that great

example of Darwinian evolution in modern history, the capitalist, the captain

of industry. And in the 1800’s, giants

would emerge who would forever link the United States with the awesome power of

industrial might and “big business”, and demonstrate the unlimited rewards that

come from ingenuity and personal initiative.

These “robber barons”, as they would later be called, would come to

display both the glory, and the tragedy, of modern capitalism.