[The following is Episode 6 of my 16-part documentary series entitled Larger than Life, about the role that beliefs play in shaping the events of our civilization.]

In

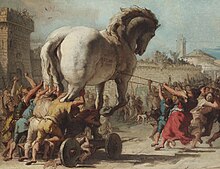

the centuries between 1600 and 1200 B.C., two great conflicts occurred that

would be forever remembered among civilizations and peoples up to modern times,

their sagas being told and retold in dramas, plays, poems, and religious texts

written in many languages, and recited in many lands. The Hebrews, under their leader Moses, would

defeat the powerful Egyptian empire in a bold slave revolt that gave them a new

beginning, and a new destiny. And the

Greeks, led by Agamemnon, Menelaeus, Odysseus, and others, would bring down the

kingdom of Troy Egypt

with him would live to cross the River Jordan into that land. Odysseus would lead his own men through

strange and hostile waters for ten years before returning to his own homeland

of Ithaca , and,

like Moses, none of those who began the journey in his company would survive to

join him there. Moses was guided and

protected by the desert God of the Hebrews; Odysseus relied upon the support of

the Greek goddess, Athena. And while two

great nations would spring from the victors in these conflicts, Israel and Greece , the losers, too, would

remain to make a mark upon history. Egypt continued

to be a great power for centuries after the Hebrew slave revolt. But the survivors that fled from the ruins of

fallen Troy

would create a new kingdom in a distant land, a kingdom so powerful that it

would rise to conquer the Greeks, the Israelites, and the Egyptians alike. The name of this new empire, mightier than

any that had risen before it, was Rome .

According to Roman legend, it was

Aeneas, a prince of Troy Troy Italy Latium Rome itself was believed to have been

founded centuries later, in 753 B.C., by Romulus Tiber River new city of their own, Rome ,

and after the death of Remus, Romulus Romulus

Romulus and Remus Reared by a She-Wolf

Seven kings ruled Rome

over a period of about two and half centuries, beginning with the legendary Romulus Athens , Sparta Athens

| The Roman Senate |

Whether the Romans had

something like Plato’s ideal in mind when they created their “republic” is not

clear – probably the most important thing on their minds at the time was to

prevent the rise of future tyrants like the one they just deposed. We’ll see in a moment that if this was their

goal it was eventually doomed to fail, but not before the republic produced

centuries of greatness for Rome Rome Rome

| Hannibal's Army |

|

| Marius and his Republican Legion |

By the time of Sulla’s

death, the Roman republic had become a sham, and the government was under the

control of the powerful, whether this power came from military might, wealth,

or the ability to sway the masses. In 59

B.C., might, wealth, and ingenuity were each personified in three men who

together would rule Rome as a triumvirate: Pompey the Great, renowned for

clearing the Mediterranean Sea of pirates and for his conquests of lands in the

east, including Syria and Judea, Crassus, an immensely wealthy man who gained

his fame in putting down a slave rebellion led by the gladiator Spartacus, and

a young, ambitious, clever, and immensely popular politician named Julius

Caesar. These three continued to pretend

that they were lawfully holding political office, first with Caesar serving as

consul, and later Pompey and Crassus, and each, when not in Rome Western Europe , but Crassus proved

to be less skillful in managing an army than he was in managing his

wealth. In a military campaign against

the Parthians, in the east, his army was badly defeated, and Crassus was

killed. The alliance between Caesar and

Pompey, which had always been an uneasy one, now broke down. When the Roman senate, under Pompey’s

leadership as sole consul, ordered Caesar to either disband his armies or be

declared a public enemy, Caesar turned his armies toward Rome Italy Pharsalus , in eastern Greece , Pompey’s armies were crushed, and Pompey

himself fled to Egypt Egypt

Julius Caesar

The rest of Caesar’s story, of his

romance with Cleopatra, his death at the hands of Brutus, Cassius, and other

senators, and the avenging of his murder by Marc Antony, his friend, Marcus

Lepidus, a former lieutenant, and Gaius Octavius, his grand-nephew, is well

chronicled in the histories and dramas of later centuries. During the short time that he had ruled, he

had been a benevolent dictator, perhaps even an enlightened one, but his rule

did seal the doom of the Roman

Republic Antony Rome Greece , Egypt , Europe, and a tiny province named Judea . And it was

during Augustus’s reign that a child would be born in Judea

who would be destined to create a world empire of his own.

At first, life under Roman rule was peaceful and not oppressive. Even as it moved into its imperial phase of government, the Roman attitude towards religion continued to be one of qualified toleration. Its subjects could freely worship any god of their choice and practice any form of religious worship, whether the religion was one that had been established in their native land, or one that was encountered either in or beyond the empire’s borders after joining the Roman family of nations. In fact, in the

|

The renewed strivings of the Jewish citizens of

And it was in the midst of

these troubled times that Jesus of Nazareth was born, that central figure of

the Christian faith, who would spend his short life preaching, healing the

sick, and gathering a band of devoted followers who would carry on his

inspiring message of hope, redemption, and universal love long after he had

departed. We are of course back once

again in uncomfortable territory as we attempt to look at the origins and

influence of Christianity with the eye of an impartial and detached observer,

because Christianity continues to be a dominant force in our culture and

civilization, and has been for nearly two thousand years. But just as we did with the Jewish Tanakh (Christian Old Testament), we

have to say from the start that the Christian New Testament, in the version that survives

today, is not without its contradictions and inconsistencies. We are provided, for example, with two

genealogies of Jesus, one from the gospel of Matthew, the other from the gospel

of Luke, which are supposed to demonstrate that he is a direct descendant of

King David, in accordance with earlier biblical prophecies about the Messiah. And while the thoroughness of these

genealogies is not unimpressive – the one in Luke traces Jesus’ ancestry all

the way back to Adam – they are inconsistent with each other. Even worse, they trace the link to King David

through Joseph, but as the gospels tell us, Joseph was not even Jesus' actual

father. The accounts of his birth in

Matthew and Luke also differ in the details.

In Matthew’s version, Joseph and Mary flee to Egypt ,

after Joseph is warned in a vision that Herod intends to kill the child, but

according to Luke, the couple returned directly to Nazareth

Jesus Giving the Sermon on the Mount

|

|

Missionary Journeys of St. Paul

Paul had been born outside of Judea, in the city of

.jpg) |

| St. Paul Preaching at Athens |

But if it had been a conscious

decision of Paul’s followers to try to secure the existence of the new movement

by distancing themselves from the Jews, the result was less than successful,

and would lead to terrible consequences.

In the eyes of the Romans, the early Christians were just another Jewish

sect, and their leader, Jesus, a claimant to a crown that could only be

perceived as subversive to the empire.

Only Caesar was the supreme ruler, and there could be no king of Judea who was not Caesar’s vassal. The fact that Jesus’ brother, James, became

his successor in the new movement must have made it seem even more obvious to

the Romans that this was an attempt to create a new dynasty, a line of kings

linked by a common family. According to

early church history, after James’s death the Romans systematically hunted down

and killed every known relative of Jesus.

Clearly, this was no idle threat to them. Meanwhile, Jerusalem Palestine Rome Rome Roman Empire , and through its

endurance, conquering it. Yet for the

Christians, this new Promised Land would be a blessing and a curse. For the many that followed the simple

teachings of Jesus, and the inspired verses of Paul, faith, hope, charity and a

vision of a universal brotherhood realized itself in the families, farms and

simple villages that abounded with the faithful. On the other hand, the new power of the

church gave free reign to the ambitious, the prejudiced, the hateful, and the

ignorant, allowing them to persecute with an unbridled violence those who they

branded as enemies of the elect: the pagan practitioners of the old Greek and

Roman faiths, the Christian heretics, and the Jews. But while Rome Rome