|

On September 23, 2019, those

attending the United Nations Climate Action Summit in New York City watched as

a 16-year-old girl, Greta Thunberg, angrily denounced their generation for

passively allowing the world to move to the brink of environmental catastrophe. Here are some of the most memorable of her

remarks:

My

message is that we'll be watching you.

This is

all wrong. I shouldn't be up here. I should be back in school on the other side

of the ocean. Yet you all come to us young people for hope. How dare you!

You have

stolen my dreams and my childhood with your empty words. And yet I'm one of the

lucky ones. People are suffering. People are dying. Entire ecosystems are collapsing.

We are in the beginning of a mass extinction, and all you can talk about is

money and fairy tales of eternal economic growth. How dare you!

. . . . You

say you hear us and that you understand the urgency. But no matter how sad and

angry I am, I do not want to believe that. Because if you really understood the

situation and still kept on failing to act, then you would be evil. And that I

refuse to believe.

. . . . You

are failing us. But the young people are starting to understand your betrayal.

The eyes of all future generations are upon you. And if you choose to fail us,

I say: We will never forgive you.

We will

not let you get away with this. Right here, right now is where we draw the

line. The world is waking up. And change is coming, whether you like it or not.

Greta Thunberg had already drawn international attention by

the time of this speech: In early 2018

she had begun organizing climate strikes at her school and, shortly after

starting the ninth grade, stopped attending classes for three weeks so that she

could stage a daily protest outside the Swedish parliament, demanding that her government

abide by its commitment to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in accordance with the

Paris Agreement of 2016. Her activism soon

drew worldwide attention, and she was invited in 2018 to speak at the United Nations

Climate Change conference. In early 2019

she participated in various student protests throughout Europe, and in August

of that year sailed to the United States from Plymouth, England in a solar-powered

boat. Later that month, she attended a hearing

hosted by the U.S. House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis, and gave her fiery

speech at the U.N. in New York the following month. Her reputation, and her following, has

continued to grow since then, as she has become something of a living symbol of

her generation’s exasperation over their elders’ responsibility for the global environmental

crisis, and relative inactivity in addressing it.

A new phrase among the younger

generation rose in popularity around the same time that Greta Thunberg and her

angry denunciation of previous generations was gaining international attention:

“Okay, Boomer”. It bitterly challenges

the wisdom of any remarks made by the “Baby Boomer” generation (those born between

the years 1946 and 1964), given the dismal legacy they have bequeathed to those

born after them, both in environmental and economic terms.

|

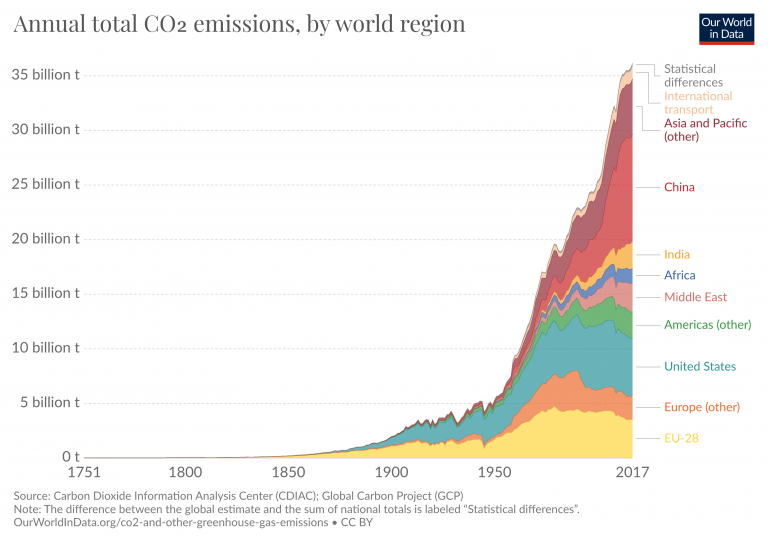

And who can disagree with

them? We are living in a world with CO2

levels at the highest they have been in at least three million years, and

about 50% higher than what they were during the millennium preceding the onset

of the Industrial Revolution. Concurrent

with this high concentration of greenhouse gas emissions has been a precipitous

rise in global temperatures, with six of the hottest years in recorded history

having occurred since 2014. This ecological

crisis, of course, is only the most discussed, but there are many others that

rival it in severity. Eighteen million acres

of forest are destroyed each year, and presently tropical forests, which once

covered 15% of the planet’s surface, now cover only 6-7%. And then there is the growing pollution of

the world’s oceans with sewage sludge, oil, toxic chemicals, and plastics, and

if the general endangerment of the ocean ecosystem from pollution isn’t bad

enough, there is the decline of marine life due to overfishing, with an

estimated one-third of the world’s fish stocks now at risk. Add to these problems the precipitous growth

in endangered species, with more than 900 plant and animal species at imminent

risk of extinction, and hundreds of others threatened, and it is clear that we

(the present generation of adults and those that preceded it) have done a

pretty thorough job of putting the earth’s ecosystem on a trajectory to catastrophe.

But we have also left the younger

generations with a huge financial burden, as we’ve sustained our own present standards

of living (and provided for our future protection with unfunded social security

and medical assistance programs) by relying upon unprecedented levels of

borrowing. In the U.S., private

(non-government) debt as a percentage of gross domestic product (a measure of the

total goods and services produced in the country) is higher than what it was in

the 1930s, during the Great Depression, and public (government) debt has grown

to more than 100% of GDP this year: a level not seen since the aftermath of

World War II, in the 1940s. The public

debts of many other nations are not far behind, with countries like England, Canada,

Spain, France all having levels exceeding 80%, while the levels in Italy, Greece,

and Japan surpass even those of the U.S.

(The public debt of Sweden, Greta Thunberg’s home country, is comparatively

less egregious, at 37% of GDP.) As if

this weren’t bad enough for America’s youth, students graduating from college

these days find themselves saddled with huge burdens of personal debt as a result

of skyrocketing education costs: something that most of their parents never had

to face.

Our collective attitude towards

this disaster of a legacy (or legacy of a disaster) tends to be at least as despicable. Most of us would rather just not think about

these problems, let alone discuss them, and the more militantly obtuse go so far

as to deny that the problems exist in the first place. Looming environmental and ecological crises

are labeled as “hoaxes” promoted by agents of a left-leaning, nefarious,

political elite, or as the naïve, misguided exaggerations of over-emotional and

scientifically-challenged “tree huggers”.

Even the more obvious economic problems associated with spiraling, out-of-control,

debt tend to be given short-shrift, even by prominent economists, as it has apparently

become unfashionable to suggest that the debt even needs to be reduced. I remember attending a panel presentation in Washington,

D.C. a few years ago that featured a well-known and highly regarded economist. Because I had heard him make reference in one

of his earlier public statements to the huge level of debt that presently

exists in this country, I naively assumed that he regarded this as a problem

that needed to be urgently addressed, and so I asked him, during the question-and-answer

session after the presentation, how he felt the problem should best be handled. He angrily retorted that he never said

the level of debt was an issue that was in urgent need of addressing, adding that

this was just the sort of idea that his critics have often tried to associate

with him.

The bitter denunciation of their

elders by today’s younger generations interestingly echoes a similar epoch in

American history: the 1960s generation, when youths on college campuses and elsewhere

collectively rose up in protest against the sins of their fathers and

mothers. Ironically, the youths who made

up that protest were Baby Boomers – the very same generation that is being ridiculed

and denounced now. And while those who participated

in the counterculture revolution of the 1960s shared with today’s angry youth many

of the same negative views of their elders – that they are insular, short-sighted,

and selfish – the protesters of the Sixties went even further: With their catchphrase “Don’t trust anyone

over thirty”, they were implying that those of the older generation were evil

as well – a charge which Greta Thunberg, at least, has been reluctant to include

among her invectives against us.

|

Those who participated in the protest

movements of the 1960s left an enduring positive legacy: making monumental strides

in the advancement of civil rights, turning the tide of popular opinion against

the mandatory conscription of young men to participate in pointless overseas

wars, and in breaking down a general cultural tendency toward stifling social conformity. Environmentalism also rose in the national

consciousness as well, as exemplified by the annual global observance of Earth

Day on April 22, which had originally been proposed in 1969 by John McConnell,

a peace activist, and which culminated in new regulations and legislation all

over the world that addressed conservation and ecological issues.

Clearly, however, whatever positive

legacy that came out of the turbulent 1960s was not enough to prevent the crises

– ecological, social, and economic – that face our world now. Was the social activism that Baby Boomers

engaged in during their youth a failure, then?

Or was it undone in the decades that followed?

I know that it is convenient to

think in terms of a “backlash”, particularly if this would allow the transference

of blame to some other, younger, generation.

It is all too easy to point out the election and popularity of President

Ronald Reagan in the 1980s as evidence of this.

A popular situation comedy in that decade, Family Ties, about a set

of idealistic parents who had been part of the Sixties counterculture movement,

now dealing with a son who admires Reagan, reads the Wall Street Journal,

and aspires to be a successful corporate capitalist, exemplified this idea. But this explanation is much too facile, and

doesn’t bear up to closer scrutiny.

First, it is naïve to paint any generation

with a broad brush and assume that all, or even most, of the members of that

generation conformed to some particular political view or held certain

attitudes in common. The hippies, student

protesters, and other youthful activists, while more visible than their peers, particularly

in the media, represented only one extreme of a spectrum of social and

political attitudes among them. (Richard

Nixon was not off the mark when he spoke of a “silent majority”, which even

existed among the young at that time.) And

it is likely that the actions of many back then – particularly in the music

industry – were motivated more by self-aggrandizement then by a genuine desire for

positive social change. Unfortunately,

the same can probably be said of Greta Thunberg’s fellow millennials – many if

not most of whom exhibit the same apathy, self-involvement, and lack of

engagement as the older generations that she decries.

And second, I think that what

happened after the Sixties was more of a dissipation of active social

engagement rather than a reaction to it.

I remember well the decade that followed, as this was the one in which I

entered my own teen years. There was a general

feeling that something remarkable had happened in those preceding turbulent

years, and that perhaps it represented the birth of a new age, which would

continue to unfold. Among the more idealistic

of those Americans who were coming of age in the 1970s (and these were still

members of the Baby Boom generation, but born in the later years), there was a sense

of obligation to somehow carry on the legacy of the Sixties, into a new phase

of social reform and evolution. But with

the Viet Nam War ended, and the resignation of a president who had come to be

seen as antithetical to everything that the Sixties had stood for, there were no

focal points of public protest – nothing that could sustain the fury and enthusiasm

which had motivated the youth during the previous decade. By the end of the 1970s, what emerged, as a consequence

of this, was a growing sense that the next phase should involve a turning inward,

and a focus on personal enlightenment which, as it expanded to include more and

more people, would reach a sort of critical mass that would naturally lead to a

better world: with greater harmony among persons and between the human race and

the environment. This new ideal was eloquently

expressed in Marilyn Ferguson’s 1980 book The Aquarian Conspiracy. In its opening chapter she writes:

A leaderless but powerful network is working to bring

about radical change in the United States.

Its members have broken with certain key elements of Western thought, and

they may have even broken continuity with history.

This network is the Aquarian Conspiracy. It is a conspiracy without a political

doctrine. Without a manifesto. With conspirators who seek power only to

disperse it, and whose strategies are pragmatic, even scientific, but whose perspective

sounds so mystical that they hesitate to discuss it. Activists asking different kinds of

questions, challenging the establishment from within.

Broader than reform, deeper than revolution, this

benign conspiracy for a new human agenda has triggered the most rapid cultural

realignment in history. The great shuddering,

irrevocable shift overtaking us is not a new political, religious, or philosophical

system. It is a new mind – the ascendance

of a startling worldview that gathers into its framework breakthrough science

and insights from earliest recorded thought.

It has been decades since I read Marilyn Ferguson’s book (with

much enthusiasm, if I recall), and so I can’t speak to the elements of her particular

program, but I do remember the general features that tended to characterize

many if not most of the “Aquarian” movements that stressed personal change and

transformation as a vehicle for general social reform. They tended to draw from a grab bag of Eastern

religions and mysticism, pop psychology, drugs (psychedelics for enlightenment,

pharmaceuticals for the treatment of conventional psychological impediments

like depression and anxiety), nutrition, exercise, occultic beliefs and

practices, self-hypnosis and auto-conditioning, and novel scientific theories –

of varying degrees of legitimacy – incorporated into new world views.

|

Some might find it ironic that –

instead of being remembered as the decade in which an Aquarian-style mass personal

transformation occurred – the 1980s is now best remembered for being the age of

the “Yuppie” (young, upwardly-mobile professional), when, in the 1987 movie Wall

Street, for example, Gordon Gecko boldly declares that “Greed is good”. But I’ve always seen a certain logic in this,

rather than an irony. After all, if the

road to general social improvement is by maximizing one’s human potential, then

how better to achieve this objective than by maximizing one’s personal standard

of living, first?

It seems that all that has survived

from that idealistic program of self-transformation are certain relics, such as

the self-help, “pulling your own strings” gurus who still appear from time to time

on public television subscription drives, and whose books grace the stands of

airport bookstores; the quasi-religious, quasi mystical audio and video series

that promise practical enlightenment; and the occultic books and artifacts sold

in the “New Age” section of bookstores and retail websites. And of course a cornucopia of pharmaceutical

drugs have evolved over the past half century to correct any mental impediments

to personal happiness – real or imaginary.

Perhaps a fraternity of genuinely enlightened

“Aquarian conspiracists” did emerge from the 1970s and 1980s, but if so, they apparently

never reached that critical mass which would produce general, positive social

transformation, or have yet to do so. And

if the fraternity does exist, I certainly must have failed to make the grade, because

I never received an invitation to join.

It must be very well concealed, in fact, because I am not aware of any of

its members among my friends, relatives, or even casual acquaintances.

And I’ve become cynical, over the

years, about how effective personal enlightenment would be as a vehicle for

saving the world. I don’t think that I

am the first to feel such cynicism. In

his 1934 book A Search in Secret India, British author Paul Brunton described

his quest to find genuine spiritually enlightened sages among the Hindu yogis, Moslem

fakirs, mystics, and other holy men in India.

But while he did encounter men and women who exhibited remarkable insights

and abilities, suggesting that they had indeed tapped into some profound higher

spiritual power, he was generally exasperated by the fact that these sages

tended to spend most of the hours of any day sitting in blissed-out trances, seemingly

oblivious to the world around them. If they

did find genuine enlightenment, it seemed to be of a very self-indulgent sort. With few exceptions, these sages seemed markedly

unconcerned about how to improve the general condition of political and economic

life in India, and when Paul Brunton pressed them for practical advice to take

back to Europe, which had descended into chaos after World War I, they merely urged

him to know himself.

But this idea that some sort of

self-transformation is necessary to fix civilization, and ultimately fix the

world, is really a carry-over of an older belief that we have all been somehow

corrupted or degraded by civilization itself.

There is a tendency to believe that there was once a Golden Age, when we

lived in harmony with nature, and with each other, but that something happened

during the course of civilization that fundamentally changed us in a pernicious

way, making us more greedy, belligerent, and exploitative, setting us against

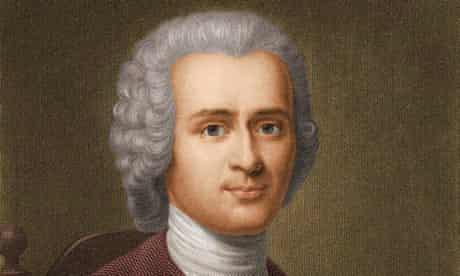

each other, and against nature itself. The idea dates at least as far back as the

Enlightenment, when Jean Jacques Rousseau declared that “Man is naturally good,

and it is by his institutions alone that men become evil.” In his essay “Discourse on the Sciences and Arts”,

written in 1750, Rousseau argued that the progress of civilization led to the

corruption of morals. Of course, there

were earlier incarnations of this idea, with romanticized conceptions of the “noble

savage” in less civilized regions of the world, and the Judeo-Christian belief

in a fall from grace in the idyllic Garden of Eden.

|

| Jean Jacques Rousseau |

Most of Rousseau’s fellow Enlightenment

thinkers did not share this view, and Voltaire, in particular, was especially

hostile to it. When Rousseau published a

subsequent essay titled “Discourse on Inequality” in 1755, in which he argued

that the commercial society of his day was fundamentally immoral, Voltaire

wrote to him:

I have

received your new book against the human race, and thank you for it.… No one

has ever employed so much intellect to persuade men to be beasts. In reading

your work one is seized with a desire to walk on all fours. However, as I have

lost that habit for more than sixty years, I feel, unfortunately, that it is

impossible for me to resume it…

Voltaire had written, nearly twenty years earlier, a

satirical poem, “The Worldling” that mocked both the secular and the religious

views of the fall from grace. In it, he

writes:

Do

you our ancestors admire,

Because they wore no rich attire?

Ease was like wealth to them unknown,

Was’t virtue? ignorance alone.

Would any fool, had he a bed,

On the bare ground have laid his head?

My fruit-eating first father, say,

In Eden how rolled time away?

Did you work for the human race,

And clasp dame Eve with close embrace!

Own that your nails you could not pare,

And that you wore disordered hair,

That you were swarthy in complexion,

And that your amorous affection

Had very little better in’t

Than downright animal instinct.

Both weary of the marriage yoke

You supped each night beneath an oak

On millet, water, and on mast,

And having finished your repast,

On the ground you were forced to lie,

Exposed to the inclement sky:

Such in the state of simple nature

Is man, a helpless, wretched creature.

Would you know in this cursed age,

Against which zealots so much rage,

To what men blessed with taste attend

In cities, how their time they spend?

The arts that charm the human mind

All at his house a welcome find;

In building it, the architect

No grace passed over with neglect.

Because they wore no rich attire?

Ease was like wealth to them unknown,

Was’t virtue? ignorance alone.

Would any fool, had he a bed,

On the bare ground have laid his head?

My fruit-eating first father, say,

In Eden how rolled time away?

Did you work for the human race,

And clasp dame Eve with close embrace!

Own that your nails you could not pare,

And that you wore disordered hair,

That you were swarthy in complexion,

And that your amorous affection

Had very little better in’t

Than downright animal instinct.

Both weary of the marriage yoke

You supped each night beneath an oak

On millet, water, and on mast,

And having finished your repast,

On the ground you were forced to lie,

Exposed to the inclement sky:

Such in the state of simple nature

Is man, a helpless, wretched creature.

Would you know in this cursed age,

Against which zealots so much rage,

To what men blessed with taste attend

In cities, how their time they spend?

The arts that charm the human mind

All at his house a welcome find;

In building it, the architect

No grace passed over with neglect.

But if civilization is not to blame – if we are no less

moral than our earliest ancestors – then what is responsible for the ecological

crisis that Greta Thunberg decries: what brought it about?

The answer is actually a very

simple one: There are too many of us –

too many human beings – on this planet.

It has been estimated that there is a total of 15.77 billion acres of habitable

land on the earth. Given that there are

presently about 7.8 billion persons alive today, this works out to nearly exactly

two acres of habitable land per person.

It sounds like a generous endowment, but if one remembers that within this

two acres per person, provision must be given for producing food, shelter, and the

other necessities – not to mention the amenities – of life, the space seems a little

more parsimonious. And then, when one also

remembers that somehow these allotments of space must be used to accommodate the

better part of a distribution of 8000 species of birds, 4000 species of mammals,

900,000 species of insects, and about 300,000 species of flowering plants,

mosses, and trees, it is obvious that things will get a little crowded, to

say the least.

Global

overpopulation is a serious, serious problem, but it has not arisen due to any

general moral failing. The very

definition of what it means to be a living thing – the essence of life itself –is

to compete for resources, consume them, grow, thrive, and reproduce. Hence, rather than being some monstrous

abortion that has poisoned and critically wounded Gaia, mother Earth, humanity

has merely played out its intended role in the web of life. Its sin – if sin it can be called – is that

it played the game of life more faithfully and more successfully than any other

species on the planet.

And so – remarkable human being

that she is – if there had been a million Greta Thunbergs living amongst us Baby

Boomers in the 1960s and 1970s – in Europe, America, Asia, and even in the developing

countries – I doubt that they would have fundamentally altered the trajectory

that led to the current state of the world.

Perhaps some additional enlightened environmental policies would have

been adopted, like the Montreal Protocol of 1987 that limited global production

of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) which had been depleting Earth’s protective

ozone layer, but these would have addressed the secondary effects of

overpopulation, and not the root cause itself.

I can think of only six ways that

might cause a reversal of global overpopulation, and most of them are

unsavory. The first is as the result of

ecological or environmental catastrophes on a large scale, such as famine, water

shortages, global warming and its consequences, or global pandemics. Closely aligned with the first is

human-induced catastrophes provoked directly by overpopulation, or indirectly

by one or more of the natural disasters outlined above. These could include widespread civil unrest,

mass destabilizing migrations, acts of extreme terrorism, and large-scale wars. Third, governments could take draconian measures

to keep their populations under control, ranging from compulsory birth control,

to forced sterilizations, to forced abortions, and finally, in the most extreme

case, to the elimination of living members of the citizenry. These all sound monstrous, of course, and beyond

contemplation, yet how many of us, if we’re completely honest with ourselves,

can deny that in our darkest moments, at least, we’ve wondered if the world

might be better off if it was rid of certain elements of the population, such

as violent and unrepentant criminals, persons prolifically producing children

that they are unable or unwilling to care for, and persons who, although

able-bodied and able-minded, seem content to live on the dole, as social parasites,

supported by friends, relatives, or government support obtained under fraudulent

circumstances. But the definition of “Unproductives”

or “Undesirables” would have to become extremely broad – not to mention

increasingly arbitrary and subjective – before such a policy would make any

appreciable impact on reducing population, and in the process, we would all inevitably

be shocked and horrified to discover the names of persons we care for appearing

on that list, and possibly eventually the appearance of our own names as well. (As a recent retiree, I would have to worry

about that as a real possibility.) And

while totalitarian governments have proved themselves to be brutally efficient

in reducing populations, they have generally not done so on the basis of “objective”

criteria, but, as in the case of the Nazis, based upon things like ethnicity, religious

affiliation, and sexual preference, or in the case of the Stalinist Soviet

Union and other Communist nations, as the result of indiscriminate mass

starvation and the execution of political enemies.

A fourth means of reducing overpopulation

would be to engineer a mass exodus from planet Earth, with the goal of colonizing

other worlds. But in spite of the enthusiasm

for extraterrestrial colonization by wealthy entrepreneurs such as Elon Musk,

this option will remain confined within the realm of science fiction well into

the future. A fifth means would be the

result of the introduction of an apex predatory species that could cull the human

herd down to ecologically sustainable levels, as has actually been done to

contain ecological imbalances involving other animals, but again this puts us well

into the realm of science fiction and fantasy.

(Science fiction, of course, has taken some even darker paths in

speculating about how humanity might deal with the population crisis, but I

will leave those to the authors of that genre.)

The sixth – and most effective –

means for population control is, ironically, the most benign, and that is to raise

the general standard of living. Adam

Smith (another Enlightenment critic of Rousseau) was one of the earliest champions

of commerce as a means of improving the general welfare, and economists of

later generations observed the link between economic development and falling

fertility rates. Today, in fact, nearly

half of the global population is living in developed nations (including Japan, Russia,

Hong Kong, and nearly all of the countries in Europe) where the fertility rate

has fallen below the replacement level.

But this leads to the further irony that among these nations the low fertility

rates have created an economic challenge, as the declining numbers of younger workers

create an increasing burden upon them to support their aging elders. As a consequence, countries are relying increasingly

upon deficit spending policies to provide for the welfare of their older

citizens, leading to the second of the twin evils – national debt – which I described

at the beginning of this blog. And in spite

of this, the world’s population continues to grow, with the total projected to

reach 11 billion by the end of this century (bringing that per person land allotment

down to 1.4 acres). This growth, of

course, is going to occur in the poorer regions of the globe, creating even

more instability and migration pressures.

When I am faced with facts and

statistics like these, my immediate reaction is one of despair, and futility. What could we in my generation have done

differently? And, more importantly, what

can all of us do, now? I sometimes try

to console myself with the thought that if consciousness – and human consciousness

in particular – is not just some accident of physics – if it is evidence of a

Divine agency at work in the universe – then surely, in spite of the succession

of crises and tragedies that have made up our collective history, the story of

humanity will ultimately have a happy ending.

But both of these attitudes – pessimism and desperate optimism – lead to

a dangerous posture of passivity – even apathy.

Why change, or try to effect change, if the ultimate outcome is out of

my – out of our – hands?

And, too, blaming all of our social

and ecological problems on overpopulation may be too simplistic. After all, it is the developed nations and

advanced economies of the planet that are responsible for the majority of toxic

emissions and other pollutants that are poisoning the ecosystem. China, the United States, and the European

Union together currently produce more than half of all production- and

consumption-based greenhouse gas emissions, and the high and upper middle

income regions of the world produce about two-thirds of global solid waste. Even if Rousseau was wrong in declaring that civilization

and commercial society has made us evil, can we at least concede that it’s made

those of us living in the more affluent nations a little more selfish,

careless, and lazy, not to mention wasteful?

Our food chain in the U.S. and other nations is dependent upon factory

farms, where the animals – which are generally no less intelligent than our

family pets – are subject to horrific conditions that, if we saw a neighbor’s pet

treated that way, would prompt us to report them to the local humane society,

and perhaps even to the police. To say

that these are a necessary evil in order to provide for our food requirements

is a hollow argument, particularly in the U.S., where obesity is a national epidemic,

and where per capita meat consumption is the highest in the world and more than

twice the global average. These troubling

facts have often caused me to consider going vegetarian, but I just can’t

resist having that next cheeseburger, or piece of fried chicken, or slice of

sausage pizza. It reminds me of that

story about St. Augustine, when he was beginning to feel the stirrings of a

religious calling, but still reaping the benefits of a lustful life. “Lord make me chaste,” he prayed, “. . . but

not yet!”

We who live in the more advanced

nations of the world have tended to fall back upon another rationale for

inaction, which is that the same economic forces that have contributed to our

affluence have also protected us from any of its negative consequences, at

least environmentally speaking. We can

produce, and consume, and consume some more, to our hearts’ content, and never

have to worry about the garbage not disappearing. We are smugly reminded that dire predictions

of environmental or ecological catastrophes made over the past several decades

never came to pass, and some of these were spectacularly wrong. The forces of free market economics, aligned

with technological development, it is argued, will continue to make any alarmist

predictions about future disasters nothing more than foolish fables. But physicist Geoffrey West, in his 2017 book

Scale, makes a compelling case for why these forces are finally reaching

the limits of their capability for pulling us back from the brink. Observing that innovation has saved us only

because the pace of innovation has been accelerating, he concludes:

. . . The

concept of business and economic cycles, and of implied cycles of innovation,

has been around for a long time and is now standard rhetoric in economics and

the business community, even though it is primarily based on broad

phenomenological deductions with little fundamental theory or mechanistic

understanding. It is implicitly taken for granted, and often taken as

unquestioned dogma, that as long as human beings remain inventive we will stay

ahead of any impending threat by continuous and ever more ingenious

innovations.

Unfortunately,

however, it’s not quite as simple as that. There’s yet another major catch, and

it’s a big one. The theory dictates that to sustain continuous growth the time

between successive innovations has to get shorter and shorter. Thus

paradigm-shifting discoveries, adaptations, and innovations must occur at an

increasingly accelerated pace. Not only does the general pace of life

inevitably quicken, but we must innovate at a faster and faster rate!

We will soon reach a point where we simply cannot innovate

fast enough to protect us from the adverse consequences of our own growth.

|

| Geoffrey West |

Returning to Greta Thunberg and her

angry denunciation of the generations that came before hers, I can only say

that while I sympathize with her and understand why she and her contemporaries

are both extremely outraged and deeply concerned, I honestly don’t know what

those in my generation could have done – when we were her age – to fundamentally

change the course of events as they unfolded over the past several decades. And of much greater concern to me personally

is that I don’t know what I should do now.

If collective social action cannot be sustained, and profound, personal

enlightenment is a fool’s errand, if not an outright sham, then how should we –

how can we – change to save the world?

When I began this blog, more than

seven years ago, its general theme was based on the questions: “What lessons can

our civilization impart to some distant future civilization, long after ours

has ceased to exist? What truths can we

pass on, about what we did right, but, perhaps more importantly, what we should

have done differently?” The second question

now looms particularly large, as it seems that the existence of our

civilization is genuinely in jeopardy. And

I am ashamed and embarrassed to say that it has left me completely stumped.

You have my deepest and most profound

admiration, Greta, and I still desperately hope that your generation and mine

can work together to come up with an answer to that question, before it’s too

late.