Recently, I happened to finish a

book that had been sitting, unread, on one of my bookshelves for decades. It had been given to me (possibly loaned to

me, I’m embarrassed to say) by a coworker, who warned me that I might be put

off by the graphic depictions in the book’s opening paragraphs. They described how a white boy on a bike happened

to wander into a black neighborhood, and was then set upon by a gang of black

youths, who beat him within an inch of his life. Their final act before leaving him lying on the

street, in a fetal position, was to pick up his bicycle and slam it down hard

on top of his limp body. Having no

interest or desire to read a book that began with an ugly account of racially-motivated violence (this was only two or three years after Reginald Denny, a truck driver,

had been beaten senseless by a black mob in retaliation for the acquittal of

Los Angeles police offers who had brutalized a black man, Rodney King, in a traffic

stop), I put the book aside.

The book is titled Makes Me Wanna Holler, and its author, Nathan McCall, was one of the black youths who had beaten up that white boy. It is the story of his life, which describes his beginnings in a working class black neighborhood, his criminal activities as a youth, his stints in prison, and the years since prison, during which he established himself as a successful writer, eventually working for the Washington Post, and authoring several books. I don’t know why I finally got around to reading it. Perhaps it’s because I thought that his life story might echo that of another biography I had recently read about a man who had risen from a troubled, working class upbringing to a successful station in life: Hillbilly Elegy, by J.D. Vance. In any case, I am glad that I finally got to it, because once I started reading it, I was unable to put it down. The account of his life, with its journey to Hell and back (with some periodic forays back into Hell) is riveting.

The climax of the story, which is also the nadir of his life, is when he is sentenced to several years in prison for committing an armed robbery of a fast food restaurant with some of his friends. He had already served time in jail for shooting a man (a young black man like himself, but who belonged to a rival clique), and so even the attorney that his mother and stepfather hired for him could not save him from doing serious time. McCall acquaints the reader with all of the horrors of prison life, including the drugs, and the violence, and the sexual predation of some of his fellow prisoners by others. And yet, it was in the midst of these horrors that he began to find guideposts for turning his life around. They came in the form of prison sages – men who in spite of their long incarceration had developed profound outlooks on life – and books that some of these sages acquainted him with.

One of the books that made a particularly strong and life-changing impression on McCall was titled Natural Psychology and Human Transformation, by Na’im Akbar, a clinical psychologist and black Muslim. The author likened the process of human transformation to that involving the maturation of a butterfly, with its three distinct stages. The first of these, corresponding to the caterpillar, he called the “hungering self or soul” and it is characterized by a lifestyle dominated by desire and self-gratification. The second stage, called “the self-accusing soul” is more contemplative, involving the activities of reflection and self-evaluation, where one steps back from the pervasive internal drives of passion, desire, and hunger, and the external conditioning that is empowered by these drives, and is able to develop both a real conscience, and a genuine (i.e., rational) consciousness. This is akin to the chrysalis stage of the insect. The final stage is that of the completed self. It is a state of transcendence, in which one finds oneself more intimately connected to and concerned with the lives of one’s fellows, and a servant to a higher Truth. This corresponds to the mature, winged butterfly, having emerged from its cocoon, and liberated from an existence confined to crawling.

It just so happened that I had been watching a video lecture series on mythology during the same time period that I was reading McCall’s book, and reading another book, titled The Hero with an African Face, on African mythology, which had been one of the recommended readings from that series. I was intrigued by how McCall’s experiences – particularly during his darkest days – paralleled the African “rite of passage” myths that were described in that other book, as well as corresponding myths in other parts of the world that were described in the lecture series. And as I reflected on my own youth, I could find a similar parallel, when my earnest desire to set my life right and start behaving like a responsible adult only arose after I had passed through a time of troubles: a personal “rite of passage”. And I remembered “rite of passage” dramas that had played out in the lives of some of my friends, when they were about that same age. I now wondered: Is there something more to myths than just the fanciful tales that underlie the superstitions of primitive peoples?

While reading Na’im Akbar’s book, Natural Psychology and Human Transformation, the following passage caught my attention:

|

The book is titled Makes Me Wanna Holler, and its author, Nathan McCall, was one of the black youths who had beaten up that white boy. It is the story of his life, which describes his beginnings in a working class black neighborhood, his criminal activities as a youth, his stints in prison, and the years since prison, during which he established himself as a successful writer, eventually working for the Washington Post, and authoring several books. I don’t know why I finally got around to reading it. Perhaps it’s because I thought that his life story might echo that of another biography I had recently read about a man who had risen from a troubled, working class upbringing to a successful station in life: Hillbilly Elegy, by J.D. Vance. In any case, I am glad that I finally got to it, because once I started reading it, I was unable to put it down. The account of his life, with its journey to Hell and back (with some periodic forays back into Hell) is riveting.

The climax of the story, which is also the nadir of his life, is when he is sentenced to several years in prison for committing an armed robbery of a fast food restaurant with some of his friends. He had already served time in jail for shooting a man (a young black man like himself, but who belonged to a rival clique), and so even the attorney that his mother and stepfather hired for him could not save him from doing serious time. McCall acquaints the reader with all of the horrors of prison life, including the drugs, and the violence, and the sexual predation of some of his fellow prisoners by others. And yet, it was in the midst of these horrors that he began to find guideposts for turning his life around. They came in the form of prison sages – men who in spite of their long incarceration had developed profound outlooks on life – and books that some of these sages acquainted him with.

One of the books that made a particularly strong and life-changing impression on McCall was titled Natural Psychology and Human Transformation, by Na’im Akbar, a clinical psychologist and black Muslim. The author likened the process of human transformation to that involving the maturation of a butterfly, with its three distinct stages. The first of these, corresponding to the caterpillar, he called the “hungering self or soul” and it is characterized by a lifestyle dominated by desire and self-gratification. The second stage, called “the self-accusing soul” is more contemplative, involving the activities of reflection and self-evaluation, where one steps back from the pervasive internal drives of passion, desire, and hunger, and the external conditioning that is empowered by these drives, and is able to develop both a real conscience, and a genuine (i.e., rational) consciousness. This is akin to the chrysalis stage of the insect. The final stage is that of the completed self. It is a state of transcendence, in which one finds oneself more intimately connected to and concerned with the lives of one’s fellows, and a servant to a higher Truth. This corresponds to the mature, winged butterfly, having emerged from its cocoon, and liberated from an existence confined to crawling.

|

It just so happened that I had been watching a video lecture series on mythology during the same time period that I was reading McCall’s book, and reading another book, titled The Hero with an African Face, on African mythology, which had been one of the recommended readings from that series. I was intrigued by how McCall’s experiences – particularly during his darkest days – paralleled the African “rite of passage” myths that were described in that other book, as well as corresponding myths in other parts of the world that were described in the lecture series. And as I reflected on my own youth, I could find a similar parallel, when my earnest desire to set my life right and start behaving like a responsible adult only arose after I had passed through a time of troubles: a personal “rite of passage”. And I remembered “rite of passage” dramas that had played out in the lives of some of my friends, when they were about that same age. I now wondered: Is there something more to myths than just the fanciful tales that underlie the superstitions of primitive peoples?

While reading Na’im Akbar’s book, Natural Psychology and Human Transformation, the following passage caught my attention:

Western psychology’s

conclusion that the outer observable nature of the human being is the best and

most accurate picture of the human being has led to many of the faulty expressions

so prevalent in European-American life.

For example, people are thoroughly preoccupied with their material life as

the essence of who they are. There is

minimal attention given to the mental, moral or spiritual aspects of life in

the Western world. In fact, the mental,

moral and spiritual aspects gain their authenticity only as instruments of achieving

certain material expressions. . . .

And a little later in the book, he continues:

There are a

couple of assumptions which we must entertain in order to understand the

concepts of “natural” psychology as opposed to Western “scientific” psychology. One of these assumptions is that human beings

are fundamentally spiritual entities whose physical forms are only reflections

or a material expression of their true spiritual nature. With this assumption, we understand that the

physical form is always an incomplete picture of what the human being is all

about. So the limitations of ideas which

guide our thought about material reality do not apply to spiritual

reality. For example, physical things

fit within the narrow confines of time and space. They can be understood as simple “cause and effect”

relationships and can be validated by the five senses. Spiritual “substance” is timeless, not confined

to any single space, and its true nature can only be inferred from the physical

manifestations. Since this is the nature

of spiritual reality then, the second assumption suggests that we can

understand the spirit through another set of skills other than those used by

scientific investigation.

There are

ways of “knowing” other than through the

observational skill used in the scientific method. One of these other observational methods is “intuition,”

where there is an emotional cue based on some unobservable indication which

comes to us through the unconscious. . . . These are not “objective” ways of

knowing, but they guide much of what we understand about the world and especially

about people. In parts of the world that

have not been consumed by reliance on the physical and the senses as its total

source of information, “intuition” is accepted as a more valuable tool for “knowing”

than “observing.”

The other

method of observation to which we must turn in seeking to understand this

spiritual nature of human beings is yet another method that has no credibility

in the grafted psychology. This method is

“revelation,” which is of course a word of blasphemy in the scientific world of

Western psychology. To them, revelation

is relegated to folklore and religion but it has no credibility in terms of

so-called “objective” reality. Most other

cultures and people other than European-Americans have always given preeminent

credibility to revelation. In the Western

world, such insights are described as superstitious at best and more likely

considered in the same vein as the hallucinations of psychotics. . . .

Now, lest one be tempted to dismiss these as the ravings of an

Afro-centric black Muslim against “European-American” (read, “white”) culture,

it should be pointed out that these insights and conclusions echo those of another

psychiatrist. More than a

quarter-century earlier, in Man and His

Symbols, Carl Jung wrote:

Because there

are innumerable things beyond the range of human understanding, we constantly

use symbolic terms to represent concepts beyond that we cannot define or fully

comprehend. This is one reason why all

religions employ symbolic language or images.

But this conscious use of symbols is only one aspect of a psychological

fact of great importance: Man also

produces symbols unconsciously and spontaneously, in the form of dreams.

Jung went on to observe that other cultures – particularly “primitive”

ones – took dreams and visions very seriously, and did not simply regard them

as, at most, symptoms of a disturbed mind. He writes:

What

psychologists call psychic identity, or “mystical participation,” has been

stripped off our world of things. But it

is exactly this halo of unconscious associations that gives a colorful and fantastic

aspect to the primitive’s world. We have

lost it to such a degree that we do not recognize it when we meet it again. With us things are kept below the threshold;

when they occasionally reappear, we even insist that something is wrong.

. . . We are

so accustomed to the apparently rational nature of our world that we scarcely

imagine anything that cannot be explained by common sense. . . .

Carl Jung, if not the first, is certainly the most famous of psychologists

who have contended that there is more to the content of our dreams than just

traces of repressed memories and desires, and hints of unresolved personal

conflicts.

|

Jung also took mythology very seriously, and later in Man and His Symbols he relates the story of a young girl who prepared a picture-book of drawings that she had composed and given as a Christmas present to her father, who happened to be a colleague of Jung’s. The drawings were based upon a series of dreams that the girl had, and consisted of strange images, including angels, monsters, pagan dancers, the moon, and a variety of animals, and many of these images involved general motifs of creation, destruction, and transformation. Although this collection of images comprised a Christmas present, Jung observed that none of the pictures had a Christian character about them, and that many of them seemed instead to allude to other philosophical, mythological, and even alchemical symbols. The girl died of an infectious disease about a year after she had presented this gift to her father, and Jung suggests that the dreams represented an intuition on the girl’s part of her transformational journey from life to death which she was about to undertake. This intuition, Jung believed, had been conveyed to her from her unconscious through archetypes not unlike those used in primitive myths to intuitively grasp the mysteries of life, death, and personal transformation.

And of the role of myth in personal

transformation during one’s lifetime, perhaps the most famous exponent of this

idea was Joseph Campbell, who appreciated Jung’s insights and applied them in his

own lifelong study of mythology. In The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Campbell

talks of the estrangement of modern man and woman, with their puerile diversions

and ambitions, from those ancient rituals which guided the human being to a

sort of spiritual maturity. “Apparently,”

he writes, “there is something in these initiatory images so necessary to the psyche

that if they are not supplied from without, through myth and ritual, they will

have to be announced again, through dream, from within – lest our energies

should remain locked in a banal, long-outmoded toy-room, at the bottom of the

sea.” And he continues:

The hero,

therefore, is the man or woman who has been able to battle past his personal

and local historical limitations to the generally valid, normally human

forms. Such a one’s visions, ideas, and

inspirations come pristine from the primary springs of human life and thought. Hence they are eloquent, not of the present,

disintegrating society and psyche, but of the unquenched source through which society

is reborn. The hero has died as a modern

man; but as eternal man – perfected, unspecific, universal man – he has been

reborn. His second solemn task and deed

therefore . . . is to return then to us, transfigured, and teach the lesson he

has learned of life renewed.

Joseph Campbell, like Na’im Akbar, saw this process of transfiguration occurring in three stages. But for Campbell, the stages of the hero’s journey are 1) a separation or departure from the familiar, commonplace existence to which one has been accustomed, 2) the encounter with trials or tests of initiation, and along with this, encounters with other (possibly supernatural) beings who help or hinder (or help, by hindering) the performance of these tests, and 3) return and reintegration, where the hero brings back the insights gained during the trial of separation (which in itself might present a new trial, if the world which is returned to is either unwelcoming, or unwelcomed, by the hero). Campbell’s first and second stages roughly correspond with Akbar’s second, chrysalis stage (with Akbar’s first stage representing that of the hero before the journey of transformation is taken), while Campbell’s third stage of return and reintegration corresponds to Akbar’s final “butterfly” stage.

As I reflected on these things, I

began to reappraise some of my longstanding personal attitudes about

mythology. I have always had a rather

pragmatic view about the beliefs that people entertain, including their religious

and mythological ones. There are the

things which we all hold to be definitely true, which includes scientific

knowledge in modern times, but also those commonsense facts which have always

been universally accepted as true. Then

there are the things which we (or some of us) believe might be true, which

would include our superstitions, speculative science such as ESP, and even perhaps

some or all of our religious beliefs.

(We might, for example, believe firmly in the Judeo-Christian God, but

doubt if some or all of the stories in the Bible actually happened, like Jonah and

the whale, or the Tower of Babel.) There

are things that we would like to believe, although we have never seen convincing

or compelling evidence to justify those beliefs. And finally, there are things which we simply

accept are beyond the limits of our knowledge, at least for the present,

although even here we might succumb to the temptation to make assumptions or

suppositions in order to fill in some of the blanks.

And out of all this, each of us

constructs a general belief about our life and our destiny, and the forces that

govern these. In addition to those concrete

facts that we use to maneuver about in our day-to-day existence, there are

those more ethereal beliefs that give us a purpose for living, and guide our process

of setting goals. We might, for example,

believe in a beneficent Creator who answers our prayers, rewards the just, and

punishes sinners – in the afterlife, if not always in this one. We might believe in karma: What goes around

comes around. And we might believe that

certain events or observations are imbued with a special importance – perhaps as

signposts to guide us in how we live our lives.

In essence, these beliefs comprise a sort of personal mythology that

provides us with hope, and confidence, and a feeling of individual

importance. But such a practice is not

limited to individuals. Entire nations, religious

groups, and peoples, as well, invest themselves in collective beliefs about

themselves that give them a sense of pride and destiny.

But ultimately, this all comes

down to what we have to believe, and what we choose to believe. And sometimes our systems of beliefs are violently

overturned. When this happens, what

often follows is a period of chaos and trauma – either personal or collective –

and we are forced to try to either somehow restore the world view that failed

us (with some necessary alterations that we hope will enable us to keep the

core intact), or construct an entirely new one that (again, we hope) will serve

us in the future. But even here, the

belief system is ultimately one of our own construction, designed explicitly to

give us a meaning and purpose for our lives.

We are admittedly limited in our efforts, since we are forced to accept

what we take to be those concrete facts of life, but beyond these, we have the

latitude to pick, and choose, and interpret those ideas that rest upon

speculation . . . or faith.

This, then, had always been my belief

– about beliefs. (A fuller exposition of

this idea was presented in “The Final Call”, August 24, 2016.) But as I began contemplating the insights

presented in Na’im Akbar’s book, along with the more general ones about mythology and archetypal

psychology by mythologists and Jungian psychologists, I began to

wonder if there are other forces that guide – or can guide – the life of a

human being beyond those that can be explained by simple cause-and-effect along

with personal psychological pragmatism.

That our life course is guided by mental

influences not readily apparent to our conscious mind is a generally accepted

insight of modern psychology, which received its most eloquent expression in the

psychoanalytic theories of Sigmund Freud and his principal followers (including,

among others, Alfred Adler, Karen Horney, and, of course, Carl Jung). An interesting variant of this idea was

described in the works of psychiatrist Eric Berne – most famously in his 1964

bestseller, Games People Play: The Psychology

of Human Relationships. One of the

insights in the book was that people tend to engage in stylized interactions

with other people that they come into contact with, to pass the time in part,

but also to meet the psychological needs of the participants for validation or

approval. At the very simplest level, these are the rote, stereotypical

banter that occurs, for example, when we encounter an acquaintance in passing,

or a coworker in the break room:

- “How’s

it going?” “Great. How’s it going with you?”

- “How

about that Patriots game last night?”

- “It looks

like more snow in the forecast.”

|

| From Games to Scripts |

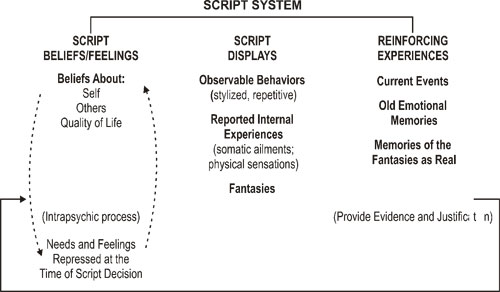

But at higher levels, these evolve into “mind games”, which are more involved interpersonal interactions that meet deeper psychological needs. That a “game” is being played is evident by the fact that this is a behavior pattern or situation that one or both persons involved seem to find themselves in repeatedly. For example, “Look what you made me do” is a game where one person tends to suffer a particular kind of misfortune that enables him or her to blame someone else for it and cause them to feel guilt and remorse. It thereby enables the victim to make someone else feel culpable – even if only temporarily – for the circumstances of their life which make them feel unhappy or unfulfilled. Games generally only constitute recurring episodes in one’s life, but there are much more complicated psychological dramas, called scripts, that could extend over days, years, or even a significant share of a lifetime. Again, a clear sign that a script is in progress in one’s life is if it parallels some similar event or pattern of events earlier in that person’s life. Although Berne’s book came out long before the movie Groundhog Day, in which a character finds that he is reliving the same day over and over again, it is suggesting the same kind of thing: that we reenact certain dramas in our life repeatedly until (or unless) we finally resolve the underlying conflict or unfulfilled psychological need. A classic example is a person who has gone through multiple marriages, but each new spouse tends to have the same kind of faults (such as alcoholism, or a tendency to violence) so that each marriage exhibits the same kinds of problems as the previous ones. Berne suggests that games and scripts are not merely limited to the individual, but can affect the conduct of peoples and nations, if not an entire civilization.

Groundhog Day

Is it possible that there are

forces other than our personal psychological drives and accidental

circumstances that guide – or could guide – our lives and our destiny? This, I think, is what is being suggested by at

least some of the mythologists: that there are things beyond the perceived

universe of time and space, cause-and-effect, that, at least potentially,

influence the course of our lives. Dreams,

myths, and visions, they suggest, are the means by which such influences reach

us. And those who are able to interpret

these and respond to them can alter the course of their own lives, and perhaps

the lives of others around them – perhaps even the destiny of entire peoples

and nations.

It is certainly interesting to

note that many of the individuals who shaped the course of nations seemed to

believe this – believed that something, be it God, or Destiny, or some other

source of inspiration and guidance, had called them to their mission in

life. Some have found inspiration in their

particular religious beliefs and practices, or just in certain profound texts. Gandhi, for example, drew inspiration from a

number of such texts, particularly the Bhagavad

Gita. But it should be noted that

not all who saw themselves as persons of destiny left a positive mark on the

world. For every Gandhi, there has been

a Hitler, and between these extremes there have been leaders who brought both

higher order and catastrophe, such as Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, and

Napoleon. And some of the paths for obtaining

profound insights seem to present special perils and risks of personal destruction,

particularly the occultic ones. Napoleon

Hill, who devoted much of his early life to studying the beliefs and behavior

patterns of the great leaders, inventors, and industrialists of his age, such

as Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, Andrew Carnegie, Woodrow Wilson, Theodore Roosevelt,

and Alexander Graham Bell, wrote that many of these successful men trusted in and

believed that they drew from a transpersonal source of ideas and inspiration,

which he labelled “Infinite Intelligence”.

Here, too, it could be argued that the successes and contributions that

stemmed from the ideas of at least some of these men were also tainted with

pernicious consequences, such as the unjust treatment of many of those employed

in Carnegie’s steel mills.

|

It is disconcerting to think that

the higher powers that guide us, both individually and collectively, might be

amoral ones, and that when we try to draw inspiration from them, it might lead

to either good or ill. It brings to mind

the mythology of the popular Star Wars

movies, with “The Force” that has both a positive side and a dark side. George Lucas, who was the original creator of

this saga, was an admirer of Joseph Campbell and his theories of the hero’s

quest as exemplified in the mythologies of our civilization. And so perhaps it would be enlightening to

return to Joseph Campbell, again, to provide a satisfactory answer to this question. Campbell believed that that there was an ultimate,

invisible source that “flowed life into the body of the world”, which he referred

to as “the World Navel”, and that the hero’s special task is to unlock and

release this flow for the benefit of humanity.

He writes, in The Hero with a Thousand

Faces:

The World

Navel, then, is ubiquitous. And since it

is the source of all existence, it yields the world’s plenitude of both good

and evil. Ugliness and beauty, sin and

virtue, pleasure and pain, are equally its production. . . . Hence the figures

worshiped in the temples of the world are by no means always beautiful, always benign,

or even necessarily virtuous. . . . And likewise, mythology does not hold as

its greatest hero the merely virtuous man.

Virtue is but the pedagogical prelude to the culminating insight, which

goes beyond all pairs of opposites. Virtue

quells the self-centered ego and makes the transpersonal centeredness possible,

but when that has been achieved, what then of pain or pleasure, vice or virtue,

of our own ego or of any other? Through

all, the transcendent force is then perceived which lives in all, in all is

wonderful, and is worthy, in all, of our profound obeisance.

For Campbell, then, the quest to lead a virtuous life, while both

necessary and noble, is not the ultimate end of the hero’s journey, for the

hero will discover, as part of that quest, that his or her greatest endeavors

will never make a Heaven of this earth, or even of one’s own existence. And yet, in spite of this, there will be a realization

that the journey, and the endeavor, was ultimately worthwhile and

life-affirming.

Returning to the life story of Nathan

McCall, it was clear, by the end of the book, that his own hero’s journey,

while leading to personal redemption for him, did not bring him into an earthly

paradise. He saw some of his friends from

the old neighborhood attempt to make that same rite of passage that he had, and

fail, backsliding into a life of crime and drug addiction. And while he succeeded in escaping the crime-ridden

environment of his youth, and entered a world that seemed to offer a comfortable

middle class existence, he soon discovered that it was a world that did not

open its arms to him in a welcoming embrace.

He now merely saw racism in a different light, in the subtle and often

not-so-subtle behaviors of his white coworkers: their fears, and suspicions,

and doubts of his abilities. He saw some

of his fellow blacks who had also made this transition get worn down, and

eventually broken, by this pernicious atmosphere of pervading hostility, the unspoken

message that “You’re not one of us. You

don’t belong here. You don’t deserve to

be here.” But he persisted, and eventually

discovered that among the “white devils” that he had been raised to distrust,

and even hate, in his youth, there were some who he could learn to trust, and

even to like.

|

The hero’s journey never ends, and with every

success comes new perils, and challenges to overcome, and perhaps even new rites

of passage to undergo. Each of us, in

our own way, if we truly aspire to be the hero or heroine of our own personal

story, must find the invisible hand that will guide us through the trials and

passages in our life, and thereby enable us to “flow life into the body of the world”.