[The following is Episode 15 of my 16-part documentary series entitled Larger than Life, about the role that beliefs play in shaping the events of our civilization.]

She is the envy of the

world. The story of her birth, as a

nation, and the establishment of its code of laws rivals the legendary

beginnings of Athens

as a democracy, under the guidance of the great lawgiver Solon. And while her government is more democratic

than the ones of classical Greece

ever were, her august institutions recall the glory of ancient republican Rome . During her brief history, slavery has been

abolished, the rights of women have been advanced, the cause of racial equality

has been espoused, and religious tolerance has become an accepted way of

life. New industries, never before seen

in the world, have been created between her shores, and scientific advances

undreamed of in earlier generations have heralded a new epoch. The diverse peoples that populate her lands

are wealthier, better educated, and healthier than those of other places and

times. And she is more powerful than any

other nation on earth. Here, for the

first time in recorded human history, is a state that has rivaled and surpassed

the legendary kingdom

of Atlantis

|

By any standard, the story of the United States of America United States United States

What is it that is so special about the United States Europe even before the

time of the American Revolution. Ancient

Athens

Nevertheless, there have been two competing strains in

our history, a light one and a dark one, which have shaped its major

events. The light one embraces the idea

of the melting pot, of a society in which all races, ethnic groups, and

religions can mix freely together in a spirit of peace and harmony, under

democratic institutions, which promote tolerance, diversity, justice, and the

general welfare. This is the vision

expressed in the message of the Statue of Liberty, and in the more inspired

writings of our nation. But there is

also a darker strain, which has played a role in our history more significant

than most would care to openly admit. It

is the idea that this great experiment in democracy, and the society in which it

manifests itself, is the product of a special people, culturally and perhaps

even biologically endowed with a greater capacity to fashion and maintain a

truly great civilization. In this view, America Old World . Between these two opposing visions, the one

of inclusion and the one of exclusion, the evolution of our culture can be seen

as a sort of expanding circle, beginning with the core of Anglo Saxon

Protestant colonists who threw off the yoke of English rule, but who in turn

reacted with consternation and ill-disguised hostility toward the Catholic

immigrants who came to America’s shores in the decades that followed. These fears were intensified during the

massive waves of Irish immigration in the 19th century, as well as

during the influx of Italians, East Europeans, and Jews who immigrated at the

turn of the century, before World War I.

Foreign religions, languages, customs, and possibly even allegiances

were seen as a threat to the grand experiment begun after the Revolutionary

War. But as each wave of immigrants

eventually assimilated to their host culture, at least to some degree, they in

turn became ardent co-defenders of the “American Way America

|

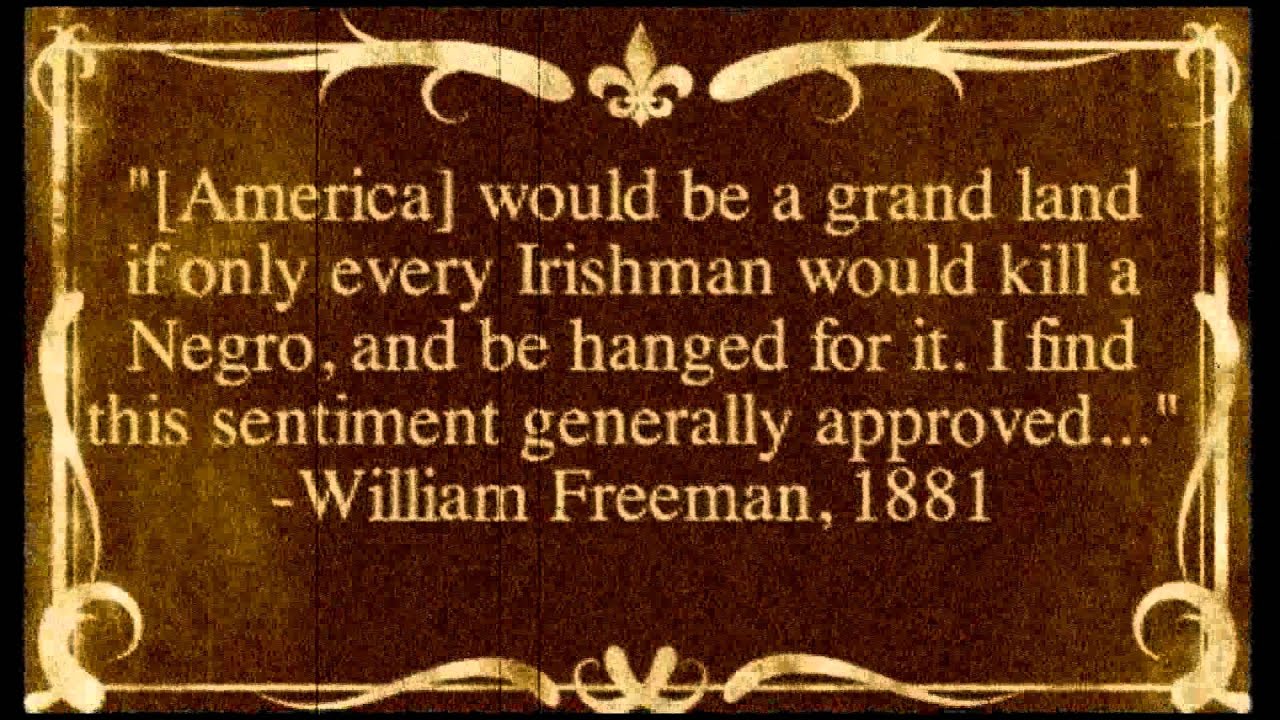

| Views and opinions such as these have sadly not been uncommon during America's history. |

Perhaps the most remarkable thing is that in the face of

this struggle, and among a collection of peoples so radically diverse in

ethnic, religious, educational, and occupational backgrounds, a distinctly

American character has appeared, that is readily recognizable to any foreigner. Ask a European how he would describe an

American, and he would probably say something like the following: superficially

friendly, gregarious, and approachable, at least on the surface, but if one

tries to get too close, to get to the real person at the core, he will

encounter a barrier that is all but insurmountable, as if there is something

that must be shielded, hid, and protected from the casual friend or

acquaintance. “Isolationist” is a phrase

commonly applied to Americans by foreigners, and it is used to convey a meaning

on many levels. Certainly there is the

well-known phenomenon of national isolationism, the recurring tendency of our

people to want to remove themselves from the affairs and concerns of the rest of

the world, and even to create a self-imposed state of ignorance. But the term also applies to that more

personal side of our character, just alluded to. Aside from a carefully selected network of

family and close friends, we strive to maintain a distance between ourselves

and those with whom we come in contact.

It has become all too common in this country for residents to remain

strangers to many of their closest neighbors, if not all of them. Consequently, we are a society of strangers,

linked together by electronic media and a set of far flung connections forged

mainly by occupational pursuits and loose family ties, capable of leading an

active social life while remaining almost entirely anonymous to the community

at large.

Europeans and Americans mark time differently.

To sketch out the history of the United States, in any

meaningful way, in just a few paragraphs, is a distinctly American undertaking –

in keeping with a tradition where we try to get to the core of something – no

matter how profound - as quickly and efficiently as possible. It is the challenge of putting together

“Cliff’s Notes” to summarize the essentials and nuances of our own collective

drama. It began, of course, with

revolution, and the idealistic experiment of creating a new government, based upon

the highest traditions and ideals of Western civilization, while grounded in

practical principles that recognized the more immediate interests of those who

would have a significant stake in the project’s outcome. Nevertheless, the constitution and federal

government that came out of this project has rightly been called a miracle, and

not necessarily because of the ingenuity of its design. An enlightened European would argue that the

parliamentary system which evolved in his land is a much more practical and

effective form of representative government, and that the Founding Fathers’

emphasis on the executive, legislative, and judicial branches as three distinct

and essential bases of power that needed to be properly balanced was an

arbitrary and even artificial construction.

Nevertheless, for all of its declared shortcomings, it has served its

purpose, converting a weak confederation of colonies into a cohesive union of

states, whose populations enjoy a voice in government and the explicit

guarantee of civil liberties and equal protection under the law. It emerged from its birthplace in Philadelphia Russia and Japan League of Nations ,

an international organization devoted to the cause of perpetual peace, but

suffered abject humiliation at home when his own country, falling back into its

traditional posture of isolationism, refused to join the organization. When the civilized world again succumbed to

the conflagration of general warfare, twenty years later, Franklin Delano

Roosevelt skillfully confronted and overcame these domestic isolationist

tendencies, leading America into a war from which it would emerge, not only

victorious, but as the dominant power in the modern international

community. The United States

The story of our history since World War II is best

understood as a story of how we attempted to live up to, and occasionally

shrank from, that task. The specter of

international Communism provided a convenient enemy by which we could continue

in our role as champion of freedom and justice against the darker forces of

totalitarianism and flawed ideology, and thereby continue framing foreign

policy as a simple doctrine of good versus evil. But this holy war became just another dubious

crusade as we found ourselves having to rely on allies of questionable

character, simply because they aligned themselves against communism, and as we

found ourselves fighting battles in remote arenas, where this country’s stake

in the outcome was far from apparent to its own people. And as the new weapons of mass destruction

which had emerged since World War II now made global annihilation a real

possibility, many questioned whether the stakes were too high to carry out any

sort of conflict whatsoever. Meanwhile,

the crusade took its toll domestically as well, in a misguided search for

domestic enemies, suspected sympathizers to the evil empire. Many began to question whether the “American

way” was really all that superior to Communism.

After all, there were tangible evidences of repression in this “free”

country, from the general emphasis on social conformity, to the outright

bigotry and racism that existed everywhere, but was particularly conspicuous in

the American south. And while the

citizens of the United

States Vietnam

But if America Europe . Washington Europe , and affect a clean break from its centuries of

war, repression, and upheaval, there also emerged a growing ambition to find

our own place in the world, which rivaled that of the other great powers. Some of our leaders have even been tempted to

follow Napoleon’s example, and extend the revolution in our nation beyond its

borders to distant lands. This has often

been attempted through diplomacy or subtle incentives, but it has, at times,

also been attempted through political subterfuge, or outright military force,

particularly in the last one hundred years, as we have begun to equate national

security at home with political stability and liberal institutions abroad. And in our conflict with Communism, an

ideology which also aspired to recast the world in its own image, we have

witnessed our foreign policy become much more pragmatic, and even cynical, a

tendency which has even outlasted Communism’s fall. Some of our national leaders have not shrunk

from supporting political despots and oppressive regimes, if it was perceived

that these could be relied upon as allies, or henchmen, in the struggle against

a more powerful enemy or ideology that threatened our national interests. In recent decades, we have seen this policy

come back to haunt us, as former pawns became troublesome and even formidable

foes in their own right, men such as Manuel Noriega, Saddam Hussein, and Osama

bin Laden. Washington

could have never foreseen that the new weapons of war, which emerged in the

twentieth century, would make it impossible for America

As America has taken a prominent role on the world stage,

it has been forced to contend with an understanding of what really drives a

national purpose, particularly as it faces rivals and enemies that seem driven by

incomprehensible, and yet unrelenting, motivations. There is of course the desire for revenge: to

redress some perceived grievance, insult, or injustice. And there is the basic desire for power, for

respect, and for acknowledgment. America America

|

If there is one way that America

In fact, in our nation, we have succeeded in bringing these dreams and myths to life in ways unimagined in earlier ages. In the nineteenth century, dime novels glorified the exploits of gunfighters in the Wild West. Comic strips, which had emerged in American newspapers in the 1890’s with “Down in Hogan’s Alley” and the Katzenjammer Kids, expanded from humor to escapist adventure yarns during the 1930’s, when this country fell into the grips of the Great Depression. A whole new crop of heroes were introduced, including Dick Tracy, Batman, Superman, Flash Gordon, and the Phantom, men and women who often had powers rivaling or even overshadowing those of the great mythical heroes of our earliest civilizations. And many of these heroes would gain even wider fame through the new mediums of radio and the cinema, as would the gun slinging legends of the Wild West from the previous century. But the cinema would also add its own contributions to this gallery of the great, like the attorney Atticus Finch of “To Kill a Mockingbird”, Indiana Jones, Gary Cooper’s abandoned but resolute sheriff Will Cane in “High Noon”, Humphrey Bogart’s courageous, jaded, innkeeper Rick Blaine of “Casablanca”, and Jimmy Stewart’s George Bailey in “It’s a Wonderful Life.” Of course, great legends need great anti-heroes as well, and our country has produced more than it’s share of these, from outlaws like Billy the Kid and Jesse James, to comic book villains such as Lex Luthor, the Joker, and Ming the Merciless, and then cinematic evildoers like Bonnie and Clyde, Hannibal Lector, Darth Vader, and the Wicked Witch of the West. The American gangster, that criminal byproduct of the Great Depression and Prohibition, became a national icon of sorts, despised and venerated at the same time in films about real ones, such as Al Capone and John Dillinger, and fictional ones, such as Don Corleone and James Cagney’s Cody Jarrett. And the cinema has even provided a modern counterpart to the darkest denizens of mythology, offering monsters such as King Kong, Frankenstein, Dracula, and the Mummy. In the 1950’s, this great landscape of mythology and legend was brought to a new outlet, television, and in the decades that followed, new sagas would be viewed in the living rooms of millions of homes across the country, and eventually throughout the world.

|

|

We tend to underestimate just what the influence of our

media has been on the rest of the world, believing that it holds our personal

histories, fables, and fantasies, with no relevance or consequence to those

living in other lands. But these

productions have transcended national boundaries, and contributed to that

strange mixture of feelings with which we are regarded by our neighbors:

admiration, awe, and fascination on the one hand; envy, resentment, contempt,

and disdain on the other. To the rest of

the world we have become the symbol of both the best and the worst of

modernity, exhibiting its technological marvels, unbridled dreams, and

continuing sense of wonder with a world of expanding possibilities, but also

its shallowness, cynicism, and growing sense of boredom in the face of escapist

entertainment that must promise greater and more immediate rewards of less and

less enduring consequence.

Our music, too, from bluegrass and country western to jazz and rock and roll, has defined who we are, and has provided a backdrop to the saga of our national history, while also entertaining and moving listeners of many lands. It has been the anthem for the downtrodden and oppressed, for racial equality, and for freedom of expression. The world watched with fascination, as Elvis Presley, like a modern Dionysus, caused young girls to scream and swoon in an ecstatic frenzy. Those that followed in his wake would take a central role in the great drama unfolding in the 1960’s, when it seemed, for a brief moment, that America was erupting in a cataclysmic but perhaps ultimately liberating transformation. It was as if the ancient, feminine, religion of self-transcendence, and of merging with the natural forces of creation, if not with the Creator itself, was finally re-emerging, to strike a crippling blow against the new mechanistic world view which had subjugated the forces of nature, and appeared to be stifling the spirit of humanity. But just at the moment where this upheaval seemed to be reaching the point of no return, when art would subjugate science, and the vast powers of commerce and government would be subdued by a new, enlightened human being, it faded and disappeared as quickly as it had arisen. In the place of music as the poetry of rebellion emerged the “entertainment industry”, which packaged and stifled artistic expression, and debased it to its most commercially appealing elements. “Modernity” triumphed, and the protest which had first found a booming voice in the Beat generation, faded and became an interesting oddity in the history of our nation.

1984

The English writer George Orwell wrote a famous book entitled “1984”, which chronicled a future age in which the forces of totalitarianism would crush the spirit of individualism. When the year came and passed, in our country, the book was treated with a slight air of condescension, as a dire prediction that never came to pass. And within the next decade, the perceived great enemy of democracy, Communism, had crumbled, as evidenced by the fall of the Soviet empire. There was a feeling of renewed optimism and faith in the promise of democracy and capitalism. But in the years since 1984, the dark, Orwellian vision of a totalitarian state has found jarring parallels in our own nation. In that book, oppression was justified by perpetual, unrelenting wars against faceless enemies, as reported in daily dispatches to the citizens of the totalitarian state. In our own time, we have seen the emergence of wars that require similar sacrifices in civil liberties, wars against nebulous enemies, and without a clearly defined objective or end. The war against drugs has enabled our government to confiscate personal property without due process of law. And the recent war against terrorism has resulted in the passage of laws that permit the government to encroach upon our privacy, allowing it to engage in acts of domestic spying and surveillance that would have been unthinkable in the past. And neither of these wars offers any promise of resolution or victory in the near future.