[The following is Episode 13 of my 16-part documentary series entitled Larger than Life, about the role that beliefs play in shaping the events of our civilization.]

He

had come to the United

States in 1848, when he was a boy, only

twelve years of age, with only five years of schooling. His father, a weaver, had left their native Scotland , with

his family, after the widespread use of a new invention, the power loom, had

robbed weavers of their profession. They

settled in Pennsylvania ,

poor and destitute, staking their future on the promise of a new life in a new

land. The boy would never return to

school. He found immediate employment at

a mill, where he earned $2 a week, and his dedication to his work brought him

rapid advancement. A year later, he was

working as a clerk at a telegraph office, and his penchant for rapidly memorizing

faces and addresses, to speed up delivery of messages, led to even more

success, including wage increases which raised his salary to $20 a month. He learned Morse code, and found a new career

as a telegraph operator, and in 1856 made his first investment, purchasing ten

shares of stock in a message and freight delivery service. Two years later, he invested in the new

invention of sleeping cars for railroads, and exclaimed, after reaping a

substantial return, “Blessed be the man who invented sleep.” In 1859, at the age of twenty-four, he was

made superintendent of the Pittsburgh division

of the Pennsylvania railroad, and two years

later, was investing in oil fields in Pennsylvania . By 1865, he was at the head of a

bridge-building company, as well as an iron company, both of which he had

formed in partnership with friends.

Profiting from a high demand for iron after the end of the American

Civil War, as well as innovations in production and sales implemented by his

employees, his fortunes continued to grow.

It was with some reluctance that he expanded his operations into the

making of steel, complaining that it took more time and was costlier to

manufacture than iron, but it was in steel that he would find his greatest and

most enduring successes. And, in 1901,

when he finally sold his steel empire and retired, it would be for the sum of

250 million dollars. From his humble

beginnings as an impoverished, poorly educated Scottish immigrant to his

phenomenal rise as a captain of industry, Andrew Carnegie would come to

symbolize the awesome, transforming power of the industrial revolution, as well

as the titanic, unforgiving power of America ’s robber barons.

The industrial revolution was like

none other in human history. It was not

a rebellion of peoples, not a political or social upheaval like the American

and French Revolutions. But its outcome

would fundamentally change the lives of individuals at all levels of society,

would radically transform the balance of power among nations, and would force

philosophers, theologians, and scientists to rethink the role of man’s place in

the world, and civilization’s ultimate destiny.

Like other revolutions, it had been brought on by a number of distinct

causes, which collectively prepared the way for a sweeping change or

upheaval. One of the most important had

been the Crusades, during the Middle Ages, when Christian armies fought to

regain the Holy Land from the Muslims. While the Crusades had ultimately failed,

they had opened new avenues for trade between the peoples of Europe and the Middle East . The

general growth of trade, in turn, had given the merchant a greater role in

society, had promoted the growth of a money economy, and had paved the way for

the downfall of feudalism. Another

cause, which also promoted the growth of trade, had been the age of

exploration. The travels of Marco Polo

in China had brought West

and East together, while the exploits of Christopher Columbus and other

Portuguese and Spanish Explorers introduced Europe to the New

World . The Renaissance,

which began in Italy Britain

It was in

But when the industrial revolution

came to the United States of

America America

|

| Cornelius Vanderbilt |

One of the earliest incarnations of

this new breed of American titan was Cornelius Vanderbilt. Born in Staten Island ,

New York in 1794, he embarked on his career at

the age of 16, when he created a ferry service to shuttle passengers and

freight between Staten Island and Manhattan New York to Chicago Richford , New York Cleveland America

John Davison Rockefeller

Although Andrew Carnegie, who came

to this country as an impoverished immigrant from Scotland

Andrew Carnegie

Carnegie’s empire would reach its

pinnacle through the efforts of another man who would loom large in his legend,

Charles M. Schwab. Schwab had also had

humble beginnings – in fact, as a youth, he had once tended Carnegie’s

horses. But in 1881, he was working in

one of Carnegie’s companies as an engineer’s assistant, and by 1892 had risen

to the rank of general superintendent at the Carnegie steel plant in Homestead , Pennsylvania New York America United States

|

| John Pierpont Morgan |

In addition to the steel industry

that he created, and his substantial charitable contributions, Carnegie left

one other, remarkable legacy. It began

with a visit from a young law student, who had found a job to support himself

through school by writing articles for a magazine on the rich and successful in

America

The young writer, Napoleon Hill,

accepted the challenge. For the next

twenty years, he interviewed many of Carnegie’s peers in business, such as

Henry Ford, Charles Schwab, Harvey Firestone, and John D. Rockefeller, along

with great inventors such as Thomas Edison and Alexander Graham Bell, and the

American presidents Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, and William Howard

Taft. The philosophy that came out of

these endeavors has appeared and reappeared in books on personal development

and business success for nearly seventy years since the publication of Napoleon

Hill’s most influential book, Think and Grow Rich, and they have become

the staple of career counselors, success gurus, and motivational speakers to

this day. At the core of Napoleon Hill’s

success philosophy was a simple but powerful idea, that a person’s thoughts and

beliefs have a pervading influence, not just over the circumstances of his own

life, but over those of his fellow human beings, in ways that he cannot

conceive or imagine. Hence, to succeed,

one must have a clear objective and purpose, and a passion for obtaining that

objective which includes a willingness to sacrifice for it, along with a belief

that its attainment is possible. But the

power of an individual’s thoughts, Napoleon Hill contended, is multiplied many

times over when it is joined in a cooperative alliance with those of others who

work in a spirit of harmony to attain mutually desired goals. And, beyond this, there is an even greater

power, that Hill referred to as Infinite Intelligence, a type of universal

storehouse of Divine power and knowledge, which is available to all who develop

the capacity to open their minds to its influence. This philosophy, with its emphasis on

personal initiative, and teamwork, coupled with a reverential if somewhat

pragmatic acknowledgement of a higher power, had a modern, but distinctly

American, cast. In a world where the

science of evolution was challenging religious faith in the traditional ideas

of Creationism and Christian altruism, a recipe for success, for making oneself

a survivor in an increasingly competitive world, seemed to be a direct answer

to the prayer of modern man. But the

success philosophy of which this recipe was a part appealed to principles

characteristic of the classic American Protestant ethic, which extolled the

virtues of self-reliance and hard work.

It embodied the American dream, in which anybody could become a success,

if only he made himself worthy of it. And

yet, in spite of its emphasis on personal power and material reward, it still

made way for a higher power, although now this higher power was not some

supreme moral agent or lawgiver, but a power in a distinctly modern sense, a

source of energy and inspiration for those who knew how to utilize it.

But there was a dark side to this

new culture of ambition, symbolized by the nineteenth century American

tycoons. For in spite of their reliance

on invention, on new technologies, and on capital, a critical component in

their success continued to be labor. But

the modern laborer, consigned to working in the new factory system, often found

that he had little more rights and privileges than the ancient serf. In theory, he could negotiate his wages,

based upon the tried and true principles of supply and demand. In practice, however, he was often a hostage to

whatever particular industry dominated his local community, forced to work for

the wages that it offered, because there was no viable alternative. His only recourse was unionization, and

collective bargaining, a system that was viewed as pernicious and subversive by

the capitalists who ran his factories.

Carnegie was no exception, although

in public pronouncements he professed to support the right of his laborers to

organize. In an essay that he wrote in

1866, he said, “The right of working men to combine and to form trade unions is

no less sacred than the right of the manufacturer to enter into associations

and conferences with his fellows. . . . My experience has been that trade

unions upon the whole are beneficial both to labor and to capital.” But his actions provided a stark contrast to

his words. In the very next year, when

iron workers held a strike at one of his plants in Pittsburgh, he brought in foreign

workers to take their place, and in 1884, he used strikebreakers at a mill in

Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania, as he did over the next three years at the same

plant. But the most memorable conflict

with union workers occurred at his steel mills in Homestead , Pennsylvania

Henry Clay Frick

|

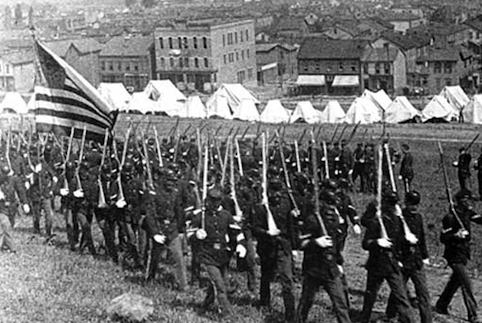

| Pennsylvania State Militia Marching to the Homestead Strike |

But Carnegie, too, had paid a price

for his role in the Homestead Atlantic . Shortly after the strike, The St. Louis

Dispatch wrote: “Three months ago Andrew Carnegie was a man to be envied. Today his is an object of mingled pity and

contempt. . . . Ten thousand ‘Carnegie Public Libraries’ would not compensate

the country for the direct and indirect evils resulting from the Homestead

Lockout.” The saga of Homestead Homestead ,

Pennsylvania , Flint ,

Michigan , and Gary , Indiana

The

Political Cartoon Featuring Teddy Roosevelt

The age of industrialism, in America Darwin Europe ,

at the dawn of the twentieth century, social Darwinism would take an even

darker turn. Here, in the writings of

radical intellectuals, the superman would have not only an indomitable personal

freedom, stronger spirit, and contempt for the weak, but also a racial

pedigree. As the promise of the new

century began to fail, betrayed by a devastating, pointless world war, many

would embrace this darker ideal of the superman, as part of a desperate attempt

to restore a sense of personal pride, in the face of a hostile world that had

lost its bearings. Others would find a

sense of purpose in equally hollow ideologies.

And at the heads of these were false prophets, demagogues, and tyrants,

who would eclipse, in their tyrannies, the greedy acts of any American robber

baron, and who would leave in their wake a toll of oppression, murder, and

destruction unrivalled by any other age in human history.