[The following is Episode 4 of my 16-part documentary series entitled Larger than Life, about the role that beliefs play in shaping the events of our civilization.]

It was a battle fought more

than three thousand years ago, in a small coastal city in Asia

Minor , but it is still remembered to this day. Two great peoples clashed in a fierce

struggle that lasted for more than ten years, and the fate of an entire kingdom

lay in the balance. On the one side, a

confederation of kings, joined by their common desire to exact vengeance on a

single enemy, and on the other side, a mighty sea power, its capital guarded by

impregnable walls and the desperate resolve of its citizens to defend it to the

bitter end. Great heroes on both sides

faced each other in combat, their swords clanging violently on massive shields,

drawing strength from a bitter rage and unyielding determination that both inspired

them and goaded them, driving them on relentlessly to fight or to die. War chariots raced across the battlefield, in

a flurry of arrows, battle cries, and screams of anguish. It was said that at times so many died that

the sheer number of their bodies clogged up entire rivers. It was even said that the gods themselves

joined in the battle, fighting alongside their mortal allies. History had never seen a war like this one. And its outcome would shape the course of

civilization. What brought the armies of

so many countries together into such a cataclysmic conflict? It was not the desire for conquest, or

wealth, or revolution. Tradition tells

us that the war was fought over a woman, Helen.

Hers was “the face the launched a thousand ships”, and their common

destination, the land where two great powers would clash and ultimately shape

their destinies, was Troy .

Two hundred years before the battle

of Troy island of Crete Greece

Although their belligerence may have distinguished

them from the Minoans, the Mycenaean peoples, like the Minoans, were also

culturally advanced. The people

practiced a high degree of craftsmanship, particularly metalwork, and engaged

in extensive trade. They were literate,

and used the same alphabet that had been adopted by later Minoan society. Perhaps not coincidently, the Mycenaean

civilization reached its peak at the same time that Minoan civilization went

into decline - about 1400 B.C. Its

cultural predominance lasted approximately 200 years until the civilization

ended abruptly around 1200 B.C. – right around the time, as a matter of fact,

that the battle with Troy

When the Mycenaean era ended, no civilization arose

to fill the void. In fact, the entire

region went into a general decline, known as the Dark Ages. This decline affected all areas of culture,

including technology, architecture, and art.

The people even forgot how to read and write. Perhaps more significantly, the general

population declined.

While we don’t know what exactly

caused the Dark Ages, it is known that two large-scale migrations were

occurring at this time. From the north

of Greece Greece into Attica, a region in the southeastern

part of Greece that would

later become the site of Athens Asia

Minor . Only one significant

technical advance occurred during this time - the replacement of bronze by iron

as the principal metal.

For these new Greeks who came to dominate the land

during the Dark Ages, history began in the year 776 B.C., a year remembered by

them as when the first Olympic games were ever held. This was their “0 AD”, and all important

events in their memory were marked off of this date. By 750 B.C., writing had been reintroduced,

but events preceding this era were only dimly remembered by the Greeks, and

survived as legends, myths, poems, epics, and songs. Two men who lived at the beginning of the new

age attempted to preserve this prehistoric legacy in poems and verses. They were Homer and Hesiod.

Homer

Homer, according to Greek tradition,

was a blind poet who lived in the eighth century B.C. He is credited with composing two epic works

of poetry, the Iliad and the Odyssey, which described events

during and immediately after the Trojan War.

His works were regarded by Greeks of later generations as authoritative

sources on theology, tradition, ancient history, and morality. They were regularly copied, memorized,

recited, and alluded to by the poets, singers, dramatists, and intellectuals of

classical Greece

The names of the Greek gods and

goddesses are still familiar to us today - Zeus, Hera, Athena, Aphrodite

(called Venus by the later Romans), Apollo – and in the stories handed down to

us of their adventures, we see parallels to the myths of the Sumerians and

Egyptians. We learn that Zeus, for

example, rose to power by overthrowing an older generation of gods, called the

Titans, of whom his own father, Cronus, had been the most powerful. And, just as we found in the myths of Sumer and Egypt Mount

Parnassus

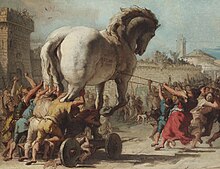

We are told that the Trojan War,

like many great sagas, began with a wedding - the wedding of King Peleus of

Pthia and Thetis, a goddess. The

ceremony was not immodest, including as it did the cream of nobility both in

Peleus’s kingdom and in neighboring kingdoms, as well as virtually all of the

gods. Only one of the immortals was not

invited - Eres, the goddess of strife.

Angered by this slight, and true to her name, Eres resolved to introduce

some trouble into the gathering. She

inscribed the phrase "For the fairest" on a golden apple and rolled

the apple into the middle of the wedding reception. Three goddesses lunged for the apple: Hera,

the queen of the Gods, Athena, the goddess of war and wisdom, and Aphrodite,

the goddess of love. They began to

quarrel among themselves over who was truly worthy of this prize and its

flattering inscription. It was resolved

that a beauty contest should be held, with a human judge selecting the

winner. A young prince of Troy , named Paris

|

| The Wedding of Thetis and Peleus . . . |

| . . . and a Wedding Crasher |

But Paris Greece Paris Troy Paris Troy

| Paris Judges a Beauty Contest |

The Greek alliance was formed under

the leadership of Agamemnon, older brother of Menelaus and king of the

Mycenaens. The combined Greek forces

gathered at the port

of Aulis Aulis . Naturally she wished to know the reason. Agamemnon explained that Iphigenia was going

to be married to Achilles, the son of King Peleus, that King whose wedding had

caused the war with Troy

|

| Principal Locations and Characters in Homer's Iliad and Odyssey |

Homer's Iliad describes important

events that occurred over the span of a few days in the Trojan War. When the epic begins, the war has been going

on for nine years. The Greeks have not

been able to overcome Troy 's walled defenses,

and have had to content themselves with raids upon neighboring villages allied

to Troy

It’s only with the help of Athena

that Achilles restrains himself from killing Agamemnon on the spot, but his

anger doesn’t pass. He removes himself

and his fellow countrymen, the Myrmidons, from the battle. He appeals to his mother, the goddess Thetis,

for aid in getting redress from Agamemnon for his insult. Thetis, in turn, carries the plea to Zeus,

king of the Gods, reminding him that Achilles is fated to die in this war, and

insisting that he deserves at least to die with honor. Zeus sympathizes with her appeal and her

son's plight, and resolves to restore honor to him by turning the tide of

battle against the Greeks, which will in turn force Agamemnon to repent for his

rash actions and beg Achilles for assistance.

The Trojans do gain the upper hand

in battle - at one point even chasing the Greeks back to their ships - and

Agamemnon sends messengers to Achilles' tent with a personal apology and a plea

for him to reenter the battle. Achilles

refuses. The Greeks continue to suffer

heavy casualties. At last, Achilles'

close friend Patroclus cannot bear to watch his fellow soldiers being

slaughtered in the battle any longer. He

pleads with Achilles to lend him his armor and let him lead the Myrmidons back

into battle. After Achilles reluctantly

agrees, Patroclus and his countrymen enter the battle and fight valiantly. The tide of battle appears to be turning

again, in favor of the Greeks, until Patroclus himself is killed at the hands

of Hector, brother of Paris

According to legend, Achilles was

himself slain shortly after the death of Hector by Hector’s brother Paris. Now Paris Troy Troy

|

Not all of the surviving Greeks

would enjoy the fruits of victory.

Agamemnon returned home to a very bitter wife Clytemnestra, who, in

collusion with her lover, murdered him in his own bathtub. (She and her lover would in turn be murdered

by her children Electra and Orestes as an act of retribution for their father's

death.) Odysseus did not see his home

until after ten years of wandering at sea, during which time he lost his entire

crew to various enemies and disasters.

Upon his return, he discovered that his home had been invaded by a

company of suitors competing for the hand of his wife, Penelope. He was not able to reclaim his home and

kingdom until murdering all of the suitors with the help of his son, two loyal

farmhands, and the goddess Athena. King

Menelaus, whose misfortunes had caused the war, returned to a more pleasant

life than these men. He’d originally

resolved to murder his wife, Helen, after coming to believe that she had

willingly joined company with Paris Troy , his anger disappeared, they reconciled, and then

they returned together as a happy couple to Menelaus' palace in Sparta

By the dawn of the Greek historic

age, when Homer was reciting his tales of the Trojan War, and Hesiod was

describing the exploits of the gods, the Greek people were no longer ruled by

kings. Instead, each city-state was

generally run by a privileged group, an elite caste of aristocrats or other

powerful men who dominated their fellow citizens. Many of these elite had gained their power

through success in business and trade, rather than military victories or

landholding. Their rule gradually became

more inflexible and harsh, particularly toward the poor and underprivileged,

and it was during this time that slavery became common in the land of Greece

As tyranny became more intolerable

among the peoples of Greece Greece , Athens

and Sparta Athens , two

great lawgivers, Solon, and later Cleisthenes, implemented a series of bold

reforms that brought an end to slavery and relief to the poor, and introduced a

new form of government that would be forever associated with Athens Sparta

The civilization of Sparta

was unlike any other in Greece Sparta , had conquered

the inhabitants in the neighboring land

of Messenia Sparta Sparta

In their ancient legends, the

Athenians and Spartans had fought and defeated great powers in distant

ages. The Athenians could pride

themselves in defeating the inhabitants of Atlantis, when the peoples of this

legendary island nation had become arrogant and cruel. And it was the Athenians, again, or rather

their champion Theseus, who humbled the mighty King Minos by destroying his

monstrous son, the Minotaur. Finally, it

was the Spartan king Menelaus who became the rallying point for a combined

Greek army to invade Troy Athens and Sparta Greece in 490

B.C., but the army was repelled by Athenian soldiers at the battle of Marathon,

and news of the victory was delivered by a runner back to Athens Greece

Together, the Athenians and Spartans

had defeated the most powerful empire of their day, but in their victory lay

the seeds of their own downfall. Athens

Alexander the Great

The legacy of the ancient Greeks remains with us to

this day. The simple but direct

questions that they asked about truth, reality, wisdom, and right conduct, as

well as many of the answers that they proposed, survive in our sciences, our

laws, and even our traditions. But there

is another legacy, equally powerful, equally revolutionary, that we bear, a

gift to us from another ancient people.

And just as the Greeks found their identity and their destiny through

the defeat of a powerful, oppressive enemy, the Hebrews would cross the

threshold of history when they successfully withstood and brought down the

awesome power of the Egyptians.